University of North Carolina Athletics

Magic Moment: Notre Dame 2008

October 5, 2017 | Football

This story is excerpted from Lee Pace's book "Football in a Forest—The Life and Times of Kenan Memorial Stadium," which is available from Johnny T-Shirt both on-line and in its Franklin Street store. The book is also available at UNC Student Stores, Chapel Hill Sports Wear and Flyleaf Books in Chapel Hill.

By Lee Pace

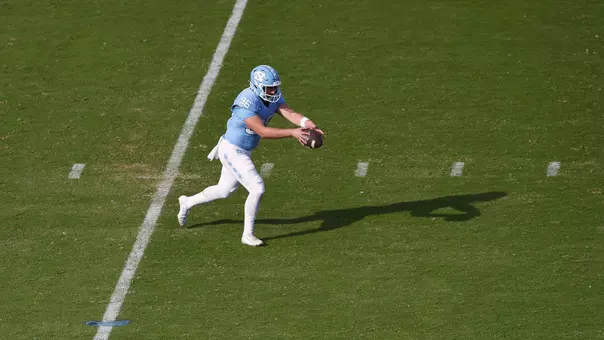

John Shoop stood almost in awe one morning in early 2009 of the image hanging on his office wall on the fourth floor of Kenan Football Center. Quarterback Cam Sexton is leaping over a diving and would-be Notre Dame tackler at the goal line. Another Fighting Irish defender comes from the right—too little, too late. Bobby Rome's arms are stretching out in celebration from the left. Fans on the north side of Kenan Stadium are on the precipice of eruption, and linemen are strewn across the turf in the background.

"I'll remember that play my whole life," said Shoop, the Tar Heel offensive coordinator from 2007-11 who seconds before it barked into his headset from the press box high above the field: Jumbo Left 415 Bronco.

"Isn't that awesome?" Shoop said enthusiastically. "I love our stadium and the crowd and all the blue in the background. That's as good a picture as there is."

Notre Dame's trip to Chapel Hill on October 11 was one of the most anticipated games in Kenan Stadium in years and marked a litmus test for the Tar Heels in Coach Butch Davis's second year in Chapel Hill to show how they stacked up. Frustrated with the inability of favorite-son John Bunting in six years to boost the program into the ACC's upper echelon, Carolina's administration fired Bunting in October 2006 and was soon pursuing Davis, who had taken Miami to great heights in the late-1990s. Davis was introduced in a late-November press conference and said: "I knew Carolina was the place I wanted to be. It had absolutely everything tantamount to building a championship team."

Demand for tickets to see the Irish was high, and 60,500 fans crammed into Kenan Stadium to set a new school record. The tension matched the buildup as the game ran deep into the third quarter. The Fighting Irish held a 24-22 lead when defensive tackle Aleric Mullins stripped QB Jimmy Clausen and recovered the ball at the Irish 42 yard-line.

On the Tar Heels' second snap after the turnover, Shaun Draughn took a pitch from Sexton and sped around the right side 38 yards for a touchdown. Two unfortunate things happened for Carolina, though—Hakeem Nicks was flagged for holding and Zack Pianalto, who threw a key block for Draughn, sprained his ankle in the celebration before the Heels realized the play was coming back. The Heels nipped and tucked their way down to the Irish four and faced a third-and-two call as the third quarter came to an end.

"A lot of people forget this play would never have happened if Shaun's touchdown hadn't been called back," says Sexton, a junior in 2008 who in 2016 lived in Charlotte and works in surgical instrument sales.

Since the Miami game two weeks earlier, the Tar Heels had consistently used Rome at fullback and Ryan Houston at tailback on short-yardage and goal-line situations. Rome and Houston together were the Tar Heels' strongest and most punishing backs, and when they entered the lineup on a short-yardage situation, everyone in the stadium—particularly Notre Dame's defenders—had a good inkling of what was coming.

So Shoop gave the Irish what they were expecting—a hand-off to Houston.

Or so everyone thought.

The "Jumbo" unit included three tight ends—two on the line of scrimmage and one on a wing to the left. Pianalto was still being attended to by trainers on the sideline, so true freshman Christian Wilson came into the game as the "H-Back" with Richard Quinn and Ed Barham the tight ends on either side of the line. It would be Wilson's first snap of college football.

The noise was deafening. From the sideline, Davis made a motion with his hands for the home crowd to turn down the volume.

"It was way different from practice," Wilson said. "During the cadence, I could hardly hear what Cam was saying. I just kind of guessed at what he was saying. I was a split second late off the ball."

On the snap of the ball, the play set up to look like a hand-off to Houston over the left side. After faking the ball to Houston, Sexton continued a full counterclockwise pirouette and ran to the right side of the field. The play in chalk would have Quinn releasing to the back of the end zone, Rome into the right of the end zone and Wilson across the middle. But reality and chalk often split, particularly if a freshman is involved.

Wilson pivoted from his three-point stance and came across the middle. After clearing the scrum at the line, he was to veer slightly upfield and into the end zone. Problem was, Wilson tripped over the left leg of center Lowell Dyer, who had extended it backward to brace himself in his block against the Irish nose guard.

"I could have scored the winning touchdown against Notre Dame on my first college play," Wilson said wistfully. "But I didn't give myself enough depth and got caught up and fell."

Sexton's swiftness afoot would be an important element of the play. He had a notion going to the line of scrimmage that he might run the ball, and the play-action fake had distracted the Notre Dame secondary and linebackers enough that, as he rolled to the flank, he saw an opening. Turning the corner out of the backfield at the 12 yard-line, Sexton was full bore intent to keep the ball. He never tucked the ball into his gut, though, and it joggled a foot from his body as he jetted toward the goal.

"Once you get on the edge, you're like a point guard in basketball," Shoop said. "If either of the DBs leave their guys in the end zone and come up to make the tackle, you can lob the ball over their head."

Sexton saw safety Kyle McCarthy (No. 28), who had been covering Rome, coming toward him at about the five and went airborne.

"Most of the time you would have dived in a situation like that," Sexton said. "It was kind of happening in slow-motion in my mind. It looked like 28 was going to go for my legs and I felt like I might have to jump for this one."

Sexton leapt at the two, McCarthy undercut him, but Sexton had plenty of energy to fly into the end zone, landing on his back in the Carolina blue paint.

Kenan Stadium exploded with one of its throatiest, most passionate roars of all time.

"I was yelling, 'I'm open, I'm open …. Touchdown!'" Rome said. "The roar was unbelievable."

"It was a huge momentum swing for us," Quinn said. "You could feel the vibration from the crowd. The ground was rumbling as we ran off the field. I've never heard it that loud."

They were the last points of the game. The final was Carolina 29, Notre Dame 24.

Bob Donnan has photographed Carolina sports for more than three decades, and his images of Tar Heel basketball have graced the cover of Sports Illustrated. One of his best photos from Kenan Stadium was a shot of Connor Barth being hugged by Jocques Dumas after making the game-winning field goal against Miami in 2004—with delirious Carolina fans in the background and a despondent Hurricane prone on the turf in the foreground. That image appeared across two pages in SI as well.

Donnan uses two cameras to shoot most sporting events—one with a telephoto zoom to capture tight action and one with a wider optic. The deeper the game goes, the more he's likely to use the wide-angle lens to capture "more atmosphere, more pieces of the puzzle," he says. He was positioned in the corner of the end zone and held the zoom lens to his eye when the play started. He snapped off three frames of Sexton rolling out with the ball. As Sexton tucked the ball and ran, Donnan shifted from one camera to the next and peeled off four frames of him scoring the touchdown.

"You knew it was an athletic move at the time, but you didn't really realize how athletic until you see each frame and see him so high up in the air," Donnan said. "I am blown away almost every week—somebody does something that is that notch above, that's really outstanding."

For two more seasons until the Davis regime ended with his firing in July 2011, the image was mounted in a first-floor hallway leading from the players' locker room to the equipment room and then to the front of the building. Coaches and players passed it and a gallery of other big-play highlights daily.

"There are a lot of emotions in this picture," Davis said. "To beat teams with mystique, you need memorable, spectacular plays. It was great improvisation on Cam's part. He had to scramble and make a play—either pass or run. He crossed the goal line and everything just erupted."

"I've seen a ton of different angles and different shots of that play, but this one is definitely my favorite," Sexton added. "The scoreboard and the crowd are in the background, I have totally cleared the Notre Dame guy. I'll never forget that play."

By Lee Pace

John Shoop stood almost in awe one morning in early 2009 of the image hanging on his office wall on the fourth floor of Kenan Football Center. Quarterback Cam Sexton is leaping over a diving and would-be Notre Dame tackler at the goal line. Another Fighting Irish defender comes from the right—too little, too late. Bobby Rome's arms are stretching out in celebration from the left. Fans on the north side of Kenan Stadium are on the precipice of eruption, and linemen are strewn across the turf in the background.

"I'll remember that play my whole life," said Shoop, the Tar Heel offensive coordinator from 2007-11 who seconds before it barked into his headset from the press box high above the field: Jumbo Left 415 Bronco.

"Isn't that awesome?" Shoop said enthusiastically. "I love our stadium and the crowd and all the blue in the background. That's as good a picture as there is."

Notre Dame's trip to Chapel Hill on October 11 was one of the most anticipated games in Kenan Stadium in years and marked a litmus test for the Tar Heels in Coach Butch Davis's second year in Chapel Hill to show how they stacked up. Frustrated with the inability of favorite-son John Bunting in six years to boost the program into the ACC's upper echelon, Carolina's administration fired Bunting in October 2006 and was soon pursuing Davis, who had taken Miami to great heights in the late-1990s. Davis was introduced in a late-November press conference and said: "I knew Carolina was the place I wanted to be. It had absolutely everything tantamount to building a championship team."

Demand for tickets to see the Irish was high, and 60,500 fans crammed into Kenan Stadium to set a new school record. The tension matched the buildup as the game ran deep into the third quarter. The Fighting Irish held a 24-22 lead when defensive tackle Aleric Mullins stripped QB Jimmy Clausen and recovered the ball at the Irish 42 yard-line.

On the Tar Heels' second snap after the turnover, Shaun Draughn took a pitch from Sexton and sped around the right side 38 yards for a touchdown. Two unfortunate things happened for Carolina, though—Hakeem Nicks was flagged for holding and Zack Pianalto, who threw a key block for Draughn, sprained his ankle in the celebration before the Heels realized the play was coming back. The Heels nipped and tucked their way down to the Irish four and faced a third-and-two call as the third quarter came to an end.

"A lot of people forget this play would never have happened if Shaun's touchdown hadn't been called back," says Sexton, a junior in 2008 who in 2016 lived in Charlotte and works in surgical instrument sales.

Since the Miami game two weeks earlier, the Tar Heels had consistently used Rome at fullback and Ryan Houston at tailback on short-yardage and goal-line situations. Rome and Houston together were the Tar Heels' strongest and most punishing backs, and when they entered the lineup on a short-yardage situation, everyone in the stadium—particularly Notre Dame's defenders—had a good inkling of what was coming.

So Shoop gave the Irish what they were expecting—a hand-off to Houston.

Or so everyone thought.

The "Jumbo" unit included three tight ends—two on the line of scrimmage and one on a wing to the left. Pianalto was still being attended to by trainers on the sideline, so true freshman Christian Wilson came into the game as the "H-Back" with Richard Quinn and Ed Barham the tight ends on either side of the line. It would be Wilson's first snap of college football.

The noise was deafening. From the sideline, Davis made a motion with his hands for the home crowd to turn down the volume.

"It was way different from practice," Wilson said. "During the cadence, I could hardly hear what Cam was saying. I just kind of guessed at what he was saying. I was a split second late off the ball."

On the snap of the ball, the play set up to look like a hand-off to Houston over the left side. After faking the ball to Houston, Sexton continued a full counterclockwise pirouette and ran to the right side of the field. The play in chalk would have Quinn releasing to the back of the end zone, Rome into the right of the end zone and Wilson across the middle. But reality and chalk often split, particularly if a freshman is involved.

Wilson pivoted from his three-point stance and came across the middle. After clearing the scrum at the line, he was to veer slightly upfield and into the end zone. Problem was, Wilson tripped over the left leg of center Lowell Dyer, who had extended it backward to brace himself in his block against the Irish nose guard.

"I could have scored the winning touchdown against Notre Dame on my first college play," Wilson said wistfully. "But I didn't give myself enough depth and got caught up and fell."

Sexton's swiftness afoot would be an important element of the play. He had a notion going to the line of scrimmage that he might run the ball, and the play-action fake had distracted the Notre Dame secondary and linebackers enough that, as he rolled to the flank, he saw an opening. Turning the corner out of the backfield at the 12 yard-line, Sexton was full bore intent to keep the ball. He never tucked the ball into his gut, though, and it joggled a foot from his body as he jetted toward the goal.

"Once you get on the edge, you're like a point guard in basketball," Shoop said. "If either of the DBs leave their guys in the end zone and come up to make the tackle, you can lob the ball over their head."

Sexton saw safety Kyle McCarthy (No. 28), who had been covering Rome, coming toward him at about the five and went airborne.

"Most of the time you would have dived in a situation like that," Sexton said. "It was kind of happening in slow-motion in my mind. It looked like 28 was going to go for my legs and I felt like I might have to jump for this one."

Sexton leapt at the two, McCarthy undercut him, but Sexton had plenty of energy to fly into the end zone, landing on his back in the Carolina blue paint.

Kenan Stadium exploded with one of its throatiest, most passionate roars of all time.

"I was yelling, 'I'm open, I'm open …. Touchdown!'" Rome said. "The roar was unbelievable."

"It was a huge momentum swing for us," Quinn said. "You could feel the vibration from the crowd. The ground was rumbling as we ran off the field. I've never heard it that loud."

They were the last points of the game. The final was Carolina 29, Notre Dame 24.

Bob Donnan has photographed Carolina sports for more than three decades, and his images of Tar Heel basketball have graced the cover of Sports Illustrated. One of his best photos from Kenan Stadium was a shot of Connor Barth being hugged by Jocques Dumas after making the game-winning field goal against Miami in 2004—with delirious Carolina fans in the background and a despondent Hurricane prone on the turf in the foreground. That image appeared across two pages in SI as well.

Donnan uses two cameras to shoot most sporting events—one with a telephoto zoom to capture tight action and one with a wider optic. The deeper the game goes, the more he's likely to use the wide-angle lens to capture "more atmosphere, more pieces of the puzzle," he says. He was positioned in the corner of the end zone and held the zoom lens to his eye when the play started. He snapped off three frames of Sexton rolling out with the ball. As Sexton tucked the ball and ran, Donnan shifted from one camera to the next and peeled off four frames of him scoring the touchdown.

"You knew it was an athletic move at the time, but you didn't really realize how athletic until you see each frame and see him so high up in the air," Donnan said. "I am blown away almost every week—somebody does something that is that notch above, that's really outstanding."

For two more seasons until the Davis regime ended with his firing in July 2011, the image was mounted in a first-floor hallway leading from the players' locker room to the equipment room and then to the front of the building. Coaches and players passed it and a gallery of other big-play highlights daily.

"There are a lot of emotions in this picture," Davis said. "To beat teams with mystique, you need memorable, spectacular plays. It was great improvisation on Cam's part. He had to scramble and make a play—either pass or run. He crossed the goal line and everything just erupted."

"I've seen a ton of different angles and different shots of that play, but this one is definitely my favorite," Sexton added. "The scoreboard and the crowd are in the background, I have totally cleared the Notre Dame guy. I'll never forget that play."

MBB: Hubert Davis Pre-Georgia Tech Press Conference

Friday, January 30

Carolina Insider - Interview with Megan Streicher (Full Segment) - January 30, 2026

Friday, January 30

WBB: Courtney Banghart Pre-NC State Media Availability

Friday, January 30

UNC Men's Basketball: Tar Heels Battle Back to Top #14 Virginia, 85-80

Saturday, January 24