University of North Carolina Athletics

Extra Points: The Legend of Danny Talbott

January 20, 2020 | Football, Featured Writers, Extra Points

By Lee Pace

It was a big day in 1954 in Battleboro, a town about seven miles north of Rocky Mount, when the local midget league all-stars hosted a basketball tournament to christen the school's new auditorium and gymnasium. Country boys always seemed to grow and mature sooner than their in-town brethren, and the Battleboro players preened in their new uniforms, supplied by St. John's Episcopal Church, and bristled with confidence.

"Some of our 10 and 11-year-olds even had hair on their chests," remembers Brent Milgrom, whose father operated a peanut farm just outside Battleboro. "I don't know why, but the boys in the rural areas were very masculine at a young age."

Milgrom and his teammates watched with interest as the players from Northside Baptist Church in Rocky Mount disembarked their bus outside the school for their game.

"We were not very impressed," Milgrom says. "We were comfortable we'd beat them. These city boys weren't coming out to our place and beating us."

Both teams started their pre-game warm-ups, with all the boys save one shooting the ball in the style of the day—the two-handed set-shot, and in the case of the better players, the one-handed push-shot that had been popularized by Wake Forest's Dickie Hemric and the teachings of coach Everett Case at N.C. State University.

One of the Northside players, however, got the attention of the Battleboro team with his ability to shoot jump shots. No one at that level wielded a jump shot.

Danny Talbott even went beyond the top of the key and was knocking down jumpers.

"He was strong and coordinated enough to do things no one else could do," Milgrom says. "We looked around at each other and said, 'We're in trouble.'"

Indeed, Northside won the game handily. Danny Talbott left an impression.

"He was special, there was no question," Milgrom says. "He could drive and score at will. But he didn't do anything fancy. He never lost control of the ball, no matter how fast he went. He was far beyond anyone else on the court."

The town of Rocky Mount and the opponents of Rocky Mount High School in football, basketball and baseball grew over the next decade to never be surprised at anything Talbott accomplished. He zigzagged across the football field for touchdowns, played safety, punted and kicked extra points. He hit last-minute shots for the Blackbird basketball team. He hit better than .400 for the baseball team, pitched right-handed and played third base and once even retired East Mecklenburg while pitching with a cast on his left arm and wrist.

He was the lynchpin of perhaps the most remarkable sports year of a single high school ever in the state of North Carolina; Rocky Mount won the state 4-A championships in football, basketball and baseball in the 1962-63 academic year. And the year after Talbott had matriculated to the University of North Carolina, the football team added a second state title in 1963.

"We had good coaching, a helluva group of athletes, and then Danny Talbott made the difference," says David Lamm, Rocky Mount High Class of 1963. "If you needed a late shot, a late hit, a big play late in the game, Danny would make it. He was a Frank Merriwell type."

Adds Marion Barnes, a fellow senior with Talbott on the 1962 state champion football team: "You knew who the stars were and who the supporting cast was. Danny was the star. He could change things on the football field, the basketball court, the baseball field. He could do things no one else could do."

Milgrom has told that story of first seeing Talbott several times recently—that one and plenty more. It probably would have come up Sunday morning as he, Jeff Beaver and Harry Bryant met at Beaver's house in Charlotte at 7 a.m. to drive to Rocky Mount to visit their old friend.

"We had three, four hours in the car we could have told Danny stories," Milgrom says.

Milgrom was a teammate of Talbott's at Rocky Mount High and later on the Carolina football team from 1963-66, Milgrom playing defense and Talbott running the offense at quarterback. Beaver, a standout high school quarterback at Myers Park High in Charlotte, had the misfortune of coming to Chapel Hill at the same time Talbott did but nonetheless developing a deep friendship despite the competition (surely a recipe for the Transfer Portal in today's college football world). And Bryant had just entered Carolina as a baseball player at Carolina in 1966 when Talbott, the Big Man on Campus, offered to pitch batting practice to a lowly and nondescript freshman.

"Other than meeting Mickey Mantle, I'd just as soon meet Danny Talbott," says Bryant, who grew up in Gastonia but had heard about the legend of Rocky Mount and its three-sport luminary. "That's what he meant to so many people in the state. He was bigger than life. I was nobody, and he offered to pitch to me. We became friends for life."

The phone rang at Beaver's house just after 7 a.m. On the line was Barnes, who lives in Rocky Mount and had been visiting Talbott, his wife Myrlene and son Bryan the last few days as Talbott was slowly slipping away after yet another setback from a nine-year battle with multiple myeloma. Barnes had the sad news that Talbott had just died. Milgrom, Beaver and Bryant said a prayer and returned to their respective homes.

"The end of an era," Milgrom says.

"I'll cherish my memories of Danny," Beaver adds. "I don't think anyone's ever been as talented as Danny in so many sports. I'm going to miss him."

***

Danny Talbott remembered later in life having a ball of some kind in his hands from the age of three, and an early growth spurt gave him several extra inches of height over other boys his age. Coaches and parents around Rocky Mount remember Talbott having "a presence at an early age," and he grew to 6-feet, 180 pounds as a high school athlete. Long-time Wilmington New Hanover Coach Leon Brogden said Talbott was "the best high school athlete I ever saw," and universities from around the nation clamored for his services during the 1962-63 school year. He considered all the ACC schools in North Carolina and also took a recruiting trip to Tennessee but eventually signed with Coach Jim Hickey and the Tar Heels.

Talbott played three sports on Tar Heel freshman teams in 1963-64—this a decade before freshman eligibility—and then gave up basketball because he didn't think he could play the sport professionally. He was the starting quarterback his sophomore year in 1964 and led the Tar Heels to an upset of Michigan State 21-15 in Kenan Stadium in the second game of the year. But he suffered bruised ribs against LSU two weeks later and was less than a hundred percent the rest of the year.

Hickey installed a spread offense in 1965 to showcase Talbott's abilities. Carolina lost at home to Michigan 31-24 in the season opener, then traveled to Ohio State. Talbott was 11-of-16 for 127 yards in leading the Tar Heels to a 14-3 upset of Coach Woody Hayes' squad. But the Tar Heels had a Jekyll-and-Hyde personality that season, playing the powerhouses tough and losing their focus against lesser teams. They followed the big win in Columbus by losing at home to lowly Virginia—"Rigor Mortis Tar Heels" screamed a headline in The Daily Tar Heel—and finished the year with a 4-6 mark. Still, Talbott led the ACC with 1,477 yards of total offense and was named player of the year.

Talbott was mentioned as a Heisman Trophy candidate entering the 1966 season, and the year was off to a rousing start with a 21-7 upset over eighth-ranked Michigan in Ann Arbor in the third game of the year. Talbott suffered a badly sprained ankle the following week at Notre Dame and was never again at full speed the rest of his senior year. Carolina slumped to 2-8, and Hickey resigned to become the athletic director at the University of Connecticut.

"If Danny had had a supporting cast, there's no telling what he'd have done," says Barnes, a Tar Heel linebacker during Talbott's era and a letterman in 1966. "He could have won the Heisman Trophy. He could play in the big-time. But he was always hurt. He never had any protection. He had a lack of support on both sides of the ball. We might have had one or two good players, but not enough of them."

Talbott was part of a remarkable run of victories the Tar Heels had in marquee games from 1960-66 under Hickey. Over that seven-year span, Carolina beat Notre Dame, Tennessee, Georgia and Michigan State within the hospitable bosom of Kenan Stadium, then ventured on the road to win at Ohio State and Michigan.

"That sure was fun," Talbott said. "It was very exciting to beat those teams, particularly when we struggled against some teams in the ACC. We just seemed to rise to the occasion for those games. It's a great thrill to think back on going to a place like Michigan and turning a crowd of 88,000 into total silence."

Talbott made first-team All-ACC three years running in baseball, finishing with a career batting average of .357 and leading Carolina to the 1966 College World Series. He hit .395 his senior year and lost the ACC batting title to teammate Charlie Carr, who edged him at .397.

"Danny was bigger than life but so humble and caring and kind," Bryant says. "I never saw him hit a home run, but I bet I saw him hit 40 doubles. He could just wear a baseball out. Hitting .395 with a wooden bat—can you imagine that?"

Talbott was drafted by the NFL's San Francisco 49ers in the 1967 draft but instead opted for pro baseball. He played one year of minor league ball—with the Baltimore Orioles' farm team in Miami—then decided to give football one more shot when his rights were acquired by the Washington Redskins. He spent three years backing up Sonny Jurgensen and Frank Ryan and "carrying Vince Lombardi's clipboard."

Talbott then returned home to Rocky Mount and enjoyed a successful career of 33 years in pharmaceutical sales, retiring in 2007. Over the years he learned to play tennis and became an accomplished player.

"Danny was just something special, he could do anything," says Bill Warren, another Rocky Mount and Carolina teammate. "He picked up tennis and before long was hitting serves with one hand and ground strokes with the other. He was absolutely the best all-around athlete I'd ever seen doing everything."

And in later years Talbott ventured into the golf arena, admitting in 2007 that was about to become the one sport he couldn't declare mastery over.

"It's the hardest game I've ever tried," he said. "That sucker is just sitting there, daring you to hit it. It's a challenge, but it's a lot of fun."

Three years later, Talbott was diagnosed with a form of cancer that primarily affects the bone marrow and can cause patients to become anemic. He returned to Chapel Hill and the N.C. Cancer Hospital numerous times over the next nine years, outliving the typical three- to four-year survival prognosis for most multiple myeloma patients. In all, he exhausted 13 chemotherapy protocols.

"When this thing hit him, we sat down and said, 'Okay, it's fourth-and-goal, it's time to make a play,'" Barnes says. "Danny never gave up. What an inspiration. If I ever was having a bad day, I'd look at Danny and tell myself to quit pouting. I never heard him complain, never heard him say, 'Why me?'"

Talbott and Myrlene, a former intensive case nurse at Nash General Hospital in Rocky Mount, often worked visits to Chapel Hill for treatment around Carolina baseball games. Boshamer Stadium in the spring became a refuge.

"Danny loved going to baseball games up to the very end," says Bryant, who watched many of them with Talbott. "He'd be up there coaching the team. He was into every move and everything going on."

The last two years of his life, Talbott was able to take some treatments closer to home. A new cancer center at Nash UNC Health Care (formerly Nash General) opened in early 2018 and was named in Talbott's honor because of what he meant to the town of Rocky Mount and to cancer patients and survivors everywhere. The fund-raising campaign was launched on the 10th day of the 10th month in 2017, and as a grassroots campaign was happy to take $10 contributions—to honor Talbott's jersey No. 10 he wore as a Blackbird and a Tar Heel.

"We are honored to have our cancer center bear Danny Talbott's name," says says Dr. L. Lee Isley, President & CEO, Nash UNC Health Care. "His perseverance and his caring spirit have inspired so many in our community—whether through athletics, community service, faith, or health. We know his legacy will live on in many ways, and we are glad to be one part of that."

Stacy Jesso, vice president and chief development officer of Nash UNC, remembers an early planning meeting for the Talbott Cancer Center when the board chairman for the hospital tied a neat bow around the concept.

"It's so refreshing to put a name on a building not because of a big check they wrote, but because he's an all-around good guy,'" Jesso says in relating the story.

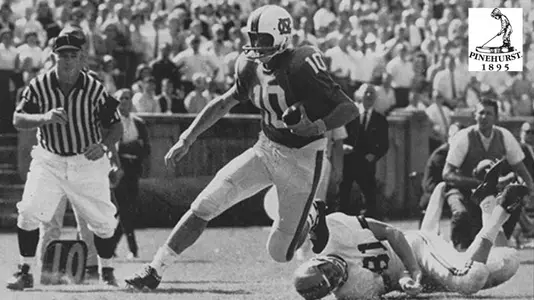

There was a sense of sadness around the facility on Monday as patients, doctors and staff walked past the large image of Talbott carrying the football for the Tar Heels on a sun-splashed day in Kenan Stadium more than half a century ago.

"There was not a more influential, humble, kind, amazing man," says Jesso, adding with a sense of regret that she didn't get a chance to tell the building's namesake last week about plans to further the reach and impact of the Danny Talbott Cancer Center in the coming years.

A Celebration of Life Service will be held for Danny Talbott on Thursday, January 23, 2020 at 11 a.m. at First Baptist Church, 200 S. Church Street, Rocky Mount, with Rev. Bill Grisham officiating. A visitation will follow the service in the Family Ministry Center.

It was a big day in 1954 in Battleboro, a town about seven miles north of Rocky Mount, when the local midget league all-stars hosted a basketball tournament to christen the school's new auditorium and gymnasium. Country boys always seemed to grow and mature sooner than their in-town brethren, and the Battleboro players preened in their new uniforms, supplied by St. John's Episcopal Church, and bristled with confidence.

"Some of our 10 and 11-year-olds even had hair on their chests," remembers Brent Milgrom, whose father operated a peanut farm just outside Battleboro. "I don't know why, but the boys in the rural areas were very masculine at a young age."

Milgrom and his teammates watched with interest as the players from Northside Baptist Church in Rocky Mount disembarked their bus outside the school for their game.

"We were not very impressed," Milgrom says. "We were comfortable we'd beat them. These city boys weren't coming out to our place and beating us."

Both teams started their pre-game warm-ups, with all the boys save one shooting the ball in the style of the day—the two-handed set-shot, and in the case of the better players, the one-handed push-shot that had been popularized by Wake Forest's Dickie Hemric and the teachings of coach Everett Case at N.C. State University.

One of the Northside players, however, got the attention of the Battleboro team with his ability to shoot jump shots. No one at that level wielded a jump shot.

Danny Talbott even went beyond the top of the key and was knocking down jumpers.

"He was strong and coordinated enough to do things no one else could do," Milgrom says. "We looked around at each other and said, 'We're in trouble.'"

Indeed, Northside won the game handily. Danny Talbott left an impression.

"He was special, there was no question," Milgrom says. "He could drive and score at will. But he didn't do anything fancy. He never lost control of the ball, no matter how fast he went. He was far beyond anyone else on the court."

The town of Rocky Mount and the opponents of Rocky Mount High School in football, basketball and baseball grew over the next decade to never be surprised at anything Talbott accomplished. He zigzagged across the football field for touchdowns, played safety, punted and kicked extra points. He hit last-minute shots for the Blackbird basketball team. He hit better than .400 for the baseball team, pitched right-handed and played third base and once even retired East Mecklenburg while pitching with a cast on his left arm and wrist.

He was the lynchpin of perhaps the most remarkable sports year of a single high school ever in the state of North Carolina; Rocky Mount won the state 4-A championships in football, basketball and baseball in the 1962-63 academic year. And the year after Talbott had matriculated to the University of North Carolina, the football team added a second state title in 1963.

"We had good coaching, a helluva group of athletes, and then Danny Talbott made the difference," says David Lamm, Rocky Mount High Class of 1963. "If you needed a late shot, a late hit, a big play late in the game, Danny would make it. He was a Frank Merriwell type."

Adds Marion Barnes, a fellow senior with Talbott on the 1962 state champion football team: "You knew who the stars were and who the supporting cast was. Danny was the star. He could change things on the football field, the basketball court, the baseball field. He could do things no one else could do."

Milgrom has told that story of first seeing Talbott several times recently—that one and plenty more. It probably would have come up Sunday morning as he, Jeff Beaver and Harry Bryant met at Beaver's house in Charlotte at 7 a.m. to drive to Rocky Mount to visit their old friend.

"We had three, four hours in the car we could have told Danny stories," Milgrom says.

Milgrom was a teammate of Talbott's at Rocky Mount High and later on the Carolina football team from 1963-66, Milgrom playing defense and Talbott running the offense at quarterback. Beaver, a standout high school quarterback at Myers Park High in Charlotte, had the misfortune of coming to Chapel Hill at the same time Talbott did but nonetheless developing a deep friendship despite the competition (surely a recipe for the Transfer Portal in today's college football world). And Bryant had just entered Carolina as a baseball player at Carolina in 1966 when Talbott, the Big Man on Campus, offered to pitch batting practice to a lowly and nondescript freshman.

"Other than meeting Mickey Mantle, I'd just as soon meet Danny Talbott," says Bryant, who grew up in Gastonia but had heard about the legend of Rocky Mount and its three-sport luminary. "That's what he meant to so many people in the state. He was bigger than life. I was nobody, and he offered to pitch to me. We became friends for life."

The phone rang at Beaver's house just after 7 a.m. On the line was Barnes, who lives in Rocky Mount and had been visiting Talbott, his wife Myrlene and son Bryan the last few days as Talbott was slowly slipping away after yet another setback from a nine-year battle with multiple myeloma. Barnes had the sad news that Talbott had just died. Milgrom, Beaver and Bryant said a prayer and returned to their respective homes.

"The end of an era," Milgrom says.

"I'll cherish my memories of Danny," Beaver adds. "I don't think anyone's ever been as talented as Danny in so many sports. I'm going to miss him."

***

Danny Talbott remembered later in life having a ball of some kind in his hands from the age of three, and an early growth spurt gave him several extra inches of height over other boys his age. Coaches and parents around Rocky Mount remember Talbott having "a presence at an early age," and he grew to 6-feet, 180 pounds as a high school athlete. Long-time Wilmington New Hanover Coach Leon Brogden said Talbott was "the best high school athlete I ever saw," and universities from around the nation clamored for his services during the 1962-63 school year. He considered all the ACC schools in North Carolina and also took a recruiting trip to Tennessee but eventually signed with Coach Jim Hickey and the Tar Heels.

Talbott played three sports on Tar Heel freshman teams in 1963-64—this a decade before freshman eligibility—and then gave up basketball because he didn't think he could play the sport professionally. He was the starting quarterback his sophomore year in 1964 and led the Tar Heels to an upset of Michigan State 21-15 in Kenan Stadium in the second game of the year. But he suffered bruised ribs against LSU two weeks later and was less than a hundred percent the rest of the year.

Hickey installed a spread offense in 1965 to showcase Talbott's abilities. Carolina lost at home to Michigan 31-24 in the season opener, then traveled to Ohio State. Talbott was 11-of-16 for 127 yards in leading the Tar Heels to a 14-3 upset of Coach Woody Hayes' squad. But the Tar Heels had a Jekyll-and-Hyde personality that season, playing the powerhouses tough and losing their focus against lesser teams. They followed the big win in Columbus by losing at home to lowly Virginia—"Rigor Mortis Tar Heels" screamed a headline in The Daily Tar Heel—and finished the year with a 4-6 mark. Still, Talbott led the ACC with 1,477 yards of total offense and was named player of the year.

Talbott was mentioned as a Heisman Trophy candidate entering the 1966 season, and the year was off to a rousing start with a 21-7 upset over eighth-ranked Michigan in Ann Arbor in the third game of the year. Talbott suffered a badly sprained ankle the following week at Notre Dame and was never again at full speed the rest of his senior year. Carolina slumped to 2-8, and Hickey resigned to become the athletic director at the University of Connecticut.

"If Danny had had a supporting cast, there's no telling what he'd have done," says Barnes, a Tar Heel linebacker during Talbott's era and a letterman in 1966. "He could have won the Heisman Trophy. He could play in the big-time. But he was always hurt. He never had any protection. He had a lack of support on both sides of the ball. We might have had one or two good players, but not enough of them."

Talbott was part of a remarkable run of victories the Tar Heels had in marquee games from 1960-66 under Hickey. Over that seven-year span, Carolina beat Notre Dame, Tennessee, Georgia and Michigan State within the hospitable bosom of Kenan Stadium, then ventured on the road to win at Ohio State and Michigan.

"That sure was fun," Talbott said. "It was very exciting to beat those teams, particularly when we struggled against some teams in the ACC. We just seemed to rise to the occasion for those games. It's a great thrill to think back on going to a place like Michigan and turning a crowd of 88,000 into total silence."

Talbott made first-team All-ACC three years running in baseball, finishing with a career batting average of .357 and leading Carolina to the 1966 College World Series. He hit .395 his senior year and lost the ACC batting title to teammate Charlie Carr, who edged him at .397.

"Danny was bigger than life but so humble and caring and kind," Bryant says. "I never saw him hit a home run, but I bet I saw him hit 40 doubles. He could just wear a baseball out. Hitting .395 with a wooden bat—can you imagine that?"

Talbott was drafted by the NFL's San Francisco 49ers in the 1967 draft but instead opted for pro baseball. He played one year of minor league ball—with the Baltimore Orioles' farm team in Miami—then decided to give football one more shot when his rights were acquired by the Washington Redskins. He spent three years backing up Sonny Jurgensen and Frank Ryan and "carrying Vince Lombardi's clipboard."

Talbott then returned home to Rocky Mount and enjoyed a successful career of 33 years in pharmaceutical sales, retiring in 2007. Over the years he learned to play tennis and became an accomplished player.

"Danny was just something special, he could do anything," says Bill Warren, another Rocky Mount and Carolina teammate. "He picked up tennis and before long was hitting serves with one hand and ground strokes with the other. He was absolutely the best all-around athlete I'd ever seen doing everything."

And in later years Talbott ventured into the golf arena, admitting in 2007 that was about to become the one sport he couldn't declare mastery over.

"It's the hardest game I've ever tried," he said. "That sucker is just sitting there, daring you to hit it. It's a challenge, but it's a lot of fun."

Three years later, Talbott was diagnosed with a form of cancer that primarily affects the bone marrow and can cause patients to become anemic. He returned to Chapel Hill and the N.C. Cancer Hospital numerous times over the next nine years, outliving the typical three- to four-year survival prognosis for most multiple myeloma patients. In all, he exhausted 13 chemotherapy protocols.

"When this thing hit him, we sat down and said, 'Okay, it's fourth-and-goal, it's time to make a play,'" Barnes says. "Danny never gave up. What an inspiration. If I ever was having a bad day, I'd look at Danny and tell myself to quit pouting. I never heard him complain, never heard him say, 'Why me?'"

Talbott and Myrlene, a former intensive case nurse at Nash General Hospital in Rocky Mount, often worked visits to Chapel Hill for treatment around Carolina baseball games. Boshamer Stadium in the spring became a refuge.

"Danny loved going to baseball games up to the very end," says Bryant, who watched many of them with Talbott. "He'd be up there coaching the team. He was into every move and everything going on."

The last two years of his life, Talbott was able to take some treatments closer to home. A new cancer center at Nash UNC Health Care (formerly Nash General) opened in early 2018 and was named in Talbott's honor because of what he meant to the town of Rocky Mount and to cancer patients and survivors everywhere. The fund-raising campaign was launched on the 10th day of the 10th month in 2017, and as a grassroots campaign was happy to take $10 contributions—to honor Talbott's jersey No. 10 he wore as a Blackbird and a Tar Heel.

"We are honored to have our cancer center bear Danny Talbott's name," says says Dr. L. Lee Isley, President & CEO, Nash UNC Health Care. "His perseverance and his caring spirit have inspired so many in our community—whether through athletics, community service, faith, or health. We know his legacy will live on in many ways, and we are glad to be one part of that."

Stacy Jesso, vice president and chief development officer of Nash UNC, remembers an early planning meeting for the Talbott Cancer Center when the board chairman for the hospital tied a neat bow around the concept.

"It's so refreshing to put a name on a building not because of a big check they wrote, but because he's an all-around good guy,'" Jesso says in relating the story.

There was a sense of sadness around the facility on Monday as patients, doctors and staff walked past the large image of Talbott carrying the football for the Tar Heels on a sun-splashed day in Kenan Stadium more than half a century ago.

"There was not a more influential, humble, kind, amazing man," says Jesso, adding with a sense of regret that she didn't get a chance to tell the building's namesake last week about plans to further the reach and impact of the Danny Talbott Cancer Center in the coming years.

A Celebration of Life Service will be held for Danny Talbott on Thursday, January 23, 2020 at 11 a.m. at First Baptist Church, 200 S. Church Street, Rocky Mount, with Rev. Bill Grisham officiating. A visitation will follow the service in the Family Ministry Center.

UNC Softball: Tar Heels Top Coastal Carolina, 8-2

Thursday, February 12

Martina Ballen: 2026 Tar Heel Trailblazer

Wednesday, February 11

Checking In with Hubert Davis - February 10, 2026

Tuesday, February 10

Carolina Insider - Interview with Nyla Harris (Full Segment) - February 6, 2026

Monday, February 09