University of North Carolina Athletics

EXTRA POINTS SPECIAL: John Bunting: The Early Days

April 2, 2001 | Extra Points

April 2, 2001

Part 1: Introduction (March 26, 2001)

Long before skateboards, goth, Allen Iverson, the Internet, Eminem, Jerry Springer, punk, the three-pointer, metal bats, sushi, the Fabulous Sports Babe and pierced tongues found their sockets in Americana, young boys the likes of John Bunting populated the landscape. They lived for The Big Three: football, basketball and baseball, depending on the colors of the leaves and the time of sunset. They ate meat and potatoes. They cropped their hair short. They wondered at times about the Russians but worried more about hitting the curve ball.

Their heroes were Unitas and Mantle, West and Cousy, Sayers and Koufax. Or in the case of Bunting, the second of three sons of Jim and Ethel Bunting of Silver Spring, Md., the idols were a third baseman named Brooks Robinson and a fullback named Jim Taylor.

Robinson--No. 5 at the hot corner for the Baltimore Orioles baseball club, just up the highway from home, winner of 16 Golden Glove awards during the O's heydey of the 1960s and '70s.

"Brooks was just Mr. Clutch," Bunting says. "He seemed like a great guy. He was a great fielder--the best to ever play that position. He had a special way he held his bat. I tried to imitate him. He had an interesting little southern drawl. He just caught my attention."

Taylor--No. 31, a workhorse fullback for Vince Lombardi's championship football teams in Green Bay in the mid-1960s.

"He was so tough, played so hard, played with such intensity," Bunting says.

Bunting is standing in the kitchen of the new home he and his wife Dawn have bought in Chapel Hill. He assumes the position of a ball-carrier, an imaginary football tucked under one arm, the other arm extended to propel defenders, one leg crooked in a running position.

"Jim Brown used to say, `I'll give you a leg, then take it away," Bunting says, executing a swift, elusive move.

He goes back to the start. His eyes widen.

"Jim Taylor said, `I'll give you a leg, and smash it through your chest," he says, powering his knee through air.

The very thought makes John Bunting smile. The man positively glows.

What better tribute to these two men than to name your one son Brooks Taylor Bunting?

Blick Drive rests amid mature hardwoods a mile or so north of the Capitol Beltway in Silver Spring. It's a comfortable street built in the 1950s to accommodate the baby boom and creeping suburbia. Split-level and two-story houses sit in neat rows with plenty of yard room for balls and energetic kids. Just around the block is Springbrook High School, and a hop, skip and jump up Highway 650 is the junior high. It was into this neighborhood that the Buntings moved their family in 1959.

"We picked it for the schools and the neighborhood," says Jim. "We thought it would be perfect for a family of boys."

gather in their living room in Silver Spring, Md., in the early 1960s. . |

Both Jim and Ethel are natives of Portland, Maine, and were living there in early marriage in the late-1930s. One of their common bonds was a love of language--Jim speaks French, Russian and some German. Ethel, whose parents were Swedish, speaks French and some Swedish. Jim was a school teacher when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, and joined the Signal Corps during World War II, using his fluency in other tongues to intercept, monitor and interpret enemy signals. That led to a post-war job in Washington with the National Security Agency, and the Buntings moved to Arlington, Va.

Jim Jr. was born in 1945, John in 1950 and Paul in 1956. "My dad had it all mapped out," says his eldest son. "As soon as one left, the other moved up to mow the grass." Jim Sr. was not a competitive athlete as a youth, though he's always been interested in sports and, at age 59, entered and finished a marathon. Both Bunting parents have won trophies for bowling. Jim is a champion senior golfer, and, at age 81, only recently yielded to the ease of a golf cart.

There was always a backdrop of games and competition in the Bunting household. One holiday season a game of "jarts"--a cross between darts and horseshoes--carried into darkness, necessitating car headlights to allow the games to continue. Ping-pong and table games of football and baseball ran long into the evenings.

Winning was very, very important, remembers Jim Jr.: "John would get mad and cry if he lost, but I was the same way. It was in the blood."

He smiles. "I've calmed down," he adds. "John's still intense."

Once Ethel came home and reported to Jim Jr. and John that her team had been successful at the bowling alley, winning two games and losing one.

"Mom, you're not mad?" John asked, incredulous.

"No, we had fun, we had a good time," she answered.

The boys looked at each other like she was from Saturn.

"They couldn't understand why I wasn't devastated that I'd lost one game," Mrs. Bunting says.

Jim Jr. was active in sports as a kid and was particularly talented in baseball and wrestling. It's this older brother that John credits for igniting the competitive fire in him and later for introducing him to the intrigue of coaching. They wrestled on the living room floor hour after hour, Jim Jr. trying various holds on his younger brother, John pushing and pulling and sweating from underneath. Perhaps it was these days that made John receptive to coach Bill Dooley's off-season mat conditioning a few years later at Chapel Hill, maybe it's one reason Bunting, 30 years later, would hire new strength coach Jeff Connors, whose program includes intense winter wrestling for football players.

One November, John watched his brother lose 21 pounds after football season to wrestle at a weight that would be best for the team, not Jim the individual. That sunk in. He hung around in awe as the high school wrestlers camped out at his house all weekend that year when a high school tournament was being held at Springbrook.

"Jim truly inspired me, particularly as a wrestler," John says. "I saw the sacrifices he made. I got caught up in the emotion of his season, in the intensity of this weekend tournament when all the guys were at our house. My brother was extremely competitive. He coached me in baseball, and if I didn't do right, he jumped my tail."

The Buntings and their friends often went to Memorial Stadium in Baltimore to watch Oriole teams managed by Earl Weaver featuring Jim Palmer and Mike Cuellar, Boog Powell and Dave McNally, and, of course, Robinson at the hot corner.

"John liked Brooks' determination," says Jim Jr. "I used to give him a hard time, reminding him that Brooks led the league in hitting into double plays. Brooks Robinson had a great glove, but he wasn't exactly fleet-footed."

"Brooks was not flashy," childhood pal Paul Fritz says. "He just made all the plays. John was like that."

John had a circle of friends who lived in the neighborhood, guys like Fritz, Frank Kaufman, Bob Ertter, Dean Drewyer and Steve Culbertson. They played The Big Three, depending on the season. They knew from early days who was the best, who was the leader.

"John was always the captain of the team, from a very early age," says Ertter. "No matter the sport, he was great. In a way, he was a tough guy to be friends with because he was so much better than everyone else. We were all in John's shadow. But he never had a swollen head over it. He was always one of the guys."

"He was a great competitor from the day we met, about the fourth grade," says Kaufman. "He had this quiet confidence in his ability. He had incredible energy. And he had a very intelligent approach to everything he applied himself to. His discipline and dedication were there from the start."

Young John cracked the first football helmet he owned in a sandlot game.

"How many nine or 10-year-olds do you know who've broken a helmet from hitting someone so hard?" asks Ertter.

Prospective football players for the junior-varsity team at Springbrook High gathered on the practice field in August, 1965, under the watchful eye of coach Jim Collier. He noticed over the first few days that one kid seemed to be at the front of the line for the tire drill and cone drill. One seemed to have more fuel left after two hours than the others. One was stronger and certainly very fast for his size--just over 6-foot and nearly 200 pounds. He seemed to set a high standard for the other kids to follow.

Collier knew he was on to something.

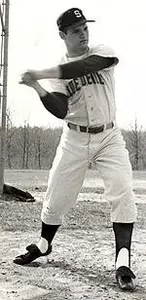

Brooks Robinson, and introduces son Brooks to his namesake. . |

"It's not anything you can explain to people. It's a sense of drive, of hunger, it's something inside that absolutely propels someone to excel. And, of course, he had the physical attributes to go with it."

The player, of course, was John Bunting.

Over the next three seasons, Bunting would inscribe the number "31" in each of his football shoes--in honor of Jim Taylor--and take the field to create loads of ills for the opposition as a fullback on offense and linebacker on defense.

It would take several defenders to tackle him.

He could shuck blockers with a vigorous forearm.

It seemed No. 43 was a part of every down.

"My dad always said you could tell if John was involved in the play," says Bob Ertter, who played defensive end. "If two or three guys were hanging onto the ball-carrier, it was John. And if the opposition ball-carrier went backward when hit, it was John making the hit.

"He made hellacious hits," he says. "It was almost as if, as a teammate, you'd shy away from a play if you saw him coming out of the corner of your eye. You didn't want him to drive into you, let alone the ball-carrier."

Adds Collier: "He was like Butkus. You didn't have to ask who hit 'em."

The collisions added up. After a game, Bunting was muddy and grassy and sometimes bloody. Collier remembers him carrying several hapless tacklers 30 yards despite a groin pull. It took a while for Bunting to get up after many play-ending whistles. He was so beat up after one road game, the team bus dropped him off at his house before going on to the high school.

"Late in some games, he could hardly put one foot in front of the other," says Ertter. "But when the ball was snapped for the next play, it was like he was shot out of a cannon. He could always reach down for that extra bit of energy."

Needless to say, Bunting was the player the other Springbrook Blue Devils looked to for inspiration and direction. Then as now, he didn't use dozens and dozens of words. A few well-chosen ones and a lot of actions did the trick.

"He led with a flick of his finger, a nod of his head," Collier says. "He wasn't very talkative, but he didn't have to use a lot of words."

It wasn't enough, however, for Bunting to be dominant physically. There was another part of all games equally as important to him.

"John was always very studious, whatever sport we were playing," says Bob Fritz. "He was the quarterback on defense. He would out-think you and outwork you."

"It was never brawn over brain with John," adds Ertter. "He always thought the sport he played."

Bunting also played point guard in basketball, another role calling for leadership and a coach-on-the-court mentality. During basketball seasons, Bunting and his buddies would recruit someone's dad to take them to nearby College Park, where they'd go to Cole Field House and watch the Maryland Terrapins and a point guard named Gary Williams.

"The Terps were our team," says Bunting. "I thought the Maryland players were great. All of a sudden one day, the Tar Heels came to town. Wow. We loved watching pre-game warm-ups. There was something impressive about Carolina when they took the court. I remember Bobby Lewis and Billy Cunningham. I loved that Carolina blue--it was a little darker shade than it is now. The shorts were satiny and shiny. That stood out.

"Then they'd rip the Terps apart. I said, `Who are these guys?' People talked about Tobacco Road. I didn't know what that meant, but it sounded like a neat place to be."

Football coaches in the Atlantic Coast Conference took something of a languid, haphazard approach to recruiting through the late-1960s. Competition for good players often didn't get spirited until after Christmas. Some players were signed whom the head coach hadn't even met. There was almost no media coverage of recruiting. It's just the way things were done in the ACC.

For one thing, the pool of potential recruits was limited. Until Freddie Saunders took the field at Wake Forest in 1967, no blacks played the game in the league. The ACC had a rule requiring a mandatory 800 SAT and 1.6 grade projection until 1970. That's why Joe Namath went to Alabama in 1961 instead of honoring his original commitment to coach Ted Nugent at Maryland.

All that changed when Bill Dooley was hired at Carolina in December, 1966, and imported the practices and mindset of the football-savvy Southeastern Conference.

Recruiting became a year-round affair at Carolina. Assistant coaches were assigned territories, just like a sales operation in any business. Dooley worked with UNC Hospitals to purchase an airplane and split the cost. He ordered his coaches to wear a dress shirt and tie on the road and visit every high school in North Carolina. He established a network of car dealers to provide complimentary automobiles to the staff. He hired a full-time recruiting coordinator, Clyde Walker, and labored long and hard with Chancellor Carlyle Sitterson for a full-time football academic advisor. Dooley got the post and hired Bill Cobey, later to come Carolina's athletics director and after that a North Carolina Congressional Representative.

"I told Clyde, `You get 'em here.' I told Bill, `You keep 'em here.' And I'm gonna coach 'em," Dooley says.

That's just the way things were done in the SEC, and Dooley knew the league. He played at Mississippi State and coached there and at Georgia.

"Bill Dooley started running 55 miles an hour in a 35 mile-an-hour zone," N.C. State coach Earle Edwards once said.

The Washington metro area was the recruiting responsibility during Dooley's first year and a half of a young graduate student and native of the D.C. area named John Atherton. A 1966 graduate of Carolina who was pursuing a masters in health and physical education and coaching football on the side, Atherton learned of John Bunting from his network of D.C.-area coaches. He traveled to Silver Spring in late September, 1967, to watch Springbrook High challenge one of the area's perennial powerhouses, Richard Montgomery High.

Montgomery won a hard-fought game, 9-6. Atherton liked what he saw from Bunting, No. 43 in the Blue Devils' home blue.

"I was impressed with his playing ability, but I was more impressed with him," says Atherton, today a personal trainer and coach in Great Falls, Va. "He had a good balance of maturity and intensity. He possessed something I call heart."

Bunting was in tears and immense pain after the game--emotional hurt because of the loss and physical hurt because of a pulled groin. Atherton saw how much the loss affected Bunting.

"Coach Atherton told us, `John's had a taste of losing. He doesn't like it at all. I like that in him,'" remembers Jim Sr.

unting, who made first-team All-Metro his senior year, received letters that fall from West Point, Virginia, Clemson, Dartmouth, Boston College, Kansas State, Michigan State, Georgia Tech and Penn State. But the most serious rivals for his services were Maryland and Carolina. Maryland coach Bob Ward had a son a year younger than Bunting at Springbrook, and all of a sudden, about midway through John's senior season, Jim Ward became "a good friend of the family," says Ethel. "He was coming by all the time."

Jim Ward told his dad of Bunting's affection for Jim Taylor, and in 1967 Taylor was playing for the New Orleans Saints in his last year in the NFL. The Saints' running backs coach and the Maryland assistant who was recruiting Bunting were good friends, so they arranged for Bunting to meet Taylor on a Sunday morning when New Orleans was in Washington to play the Redskins. Also in town that weekend was Paul Hornung, the retired Packers halfback who was good friends with Taylor.

Bunting had the thrill of his young life to sit down between these two NFL greats. It was the first time someone had paid more attention to the workhorse Taylor over the blond and flashy Hornung.

"I just stared at Jim Taylor," Bunting remembers.

Maryland was also schmoozing Bunting's girlfriend, Ren?, who was a year younger than John. One of the Maryland coaches personally took Ren? on a tour of the Maryland campus.

"John's dad told me everything that was going on," Atherton says. "So he set up a dinner at their home when Ren? would be there. I walked in and saw this pretty little blonde-haired gal and said, `Looks like I've been recruiting the wrong person.'"

Unfortunately for Ward and the Terrapins, Bunting was already smitten by the University of North Carolina. He signed the official letter-of-intent in February, 1968, and became one of 45 members of Dooley's first full-fledged class of recruits garnered under his aggressive recruiting system.

"John was what you'd call a very, very, very good prospect," Dooley says. "He's the kind of player we had to have if we were going to win championships."

Lee Pace, editor and publisher for 11 years of Extra Points, a newsletter devoted to the careful study of Tar Heel football, has interviewed dozens of family members, former teammates, players and coaches who have touched and been touched by Bunting for this exclusive series of articles. From his youth in Silver Spring, Md., to his days as a Tar Heel from 1968-71, from his days as a Philadelphia Eagle to his start in the coaching business at Rowan University, you'll relive the influences and special moments that have shaped Bunting's life over the next several installments of "The Bunting Era Dawns For Carolina."

Next Week: John Bunting As A Tar Heel

Part 1: Introduction (March 26, 2001)

Thanks to the following businesses and individuals who have helped fund this series on John Bunting:

UNC Dept. of Athletics

The Educational Foundation Inc.

Gayle Bomar, IJL Wachovia

John Anderson, General Shale Brick

Paul Miller, Quixtar

John Cowell, The Home Team