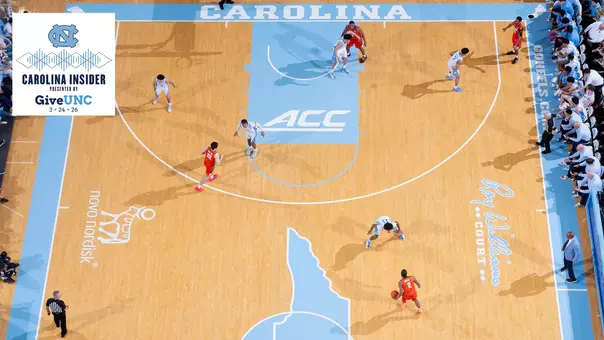

University of North Carolina Athletics

Lucas: The Sounds Of Defense

March 23, 2008 | Men's Basketball

March 23, 2008

By Adam Lucas

RALEIGH--Sometimes, Marcus Ginyard uses his eyes to evaluate his defense. Sunday evening, he was able to use his ears.

Late in the first half, he was--as usual--shadowing Arkansas standout Sonny Weems. You remember Weems, he of the 15.0 scoring average and 31 points on Thursday night against Indiana. A first-team All-SEC pick, Weems is normally more slippery than the absurd NCAA midcourt logos.

The stat sheet says Weems posted a team-high 19 points against the Tar Heels. The stat sheet is deceiving. Those were perhaps the most inconsequential 19 points in basketball history. And only seven of those points came when he was being guarded face-to-face by Ginyard: five points on jumpers and two on a layup when Ginyard slipped.

But on a night when Carolina had a historic offensive outburst, the Tar Heel defensive ace does not need the stat sheet to evaluate his effort. He got all the confirmation he needed late in the first half.

"I was guarding Weems on a curl and he got the ball and then passed it really quickly," Ginyard said. "I heard his teammates yell, `Come on, Weems!' To hear his teammates getting on him like that was a sure sign things weren't going the way he wanted them to."

Sometimes it's hard to know for sure that defense is working. When you play a great 30 seconds of defense and your man still nails a jumper over an outstretched arm, that's discouraging. But the sweet sound of dissension among teammates is one of the best defensive indicators available.

The fact that Weems scored 31 on Friday electrified the Razorbacks. The fact that he was erased on Sunday stultified them.

These days, we've been conditioned to believe that good defense equates to using your hands. Think about it. We laud "defenders" who block shots or rack up steals. That's not defense. That's just statistics, and sometimes the two are very different.

Defense is not about pulling, poking, forearming, or flopping. It's about awareness, balance, and anticipation. Considering the current climate of contact in college basketball, it might be shocking that many times good defense does not even require physical contact.

When it's played well, it can be game-changing. Without Weems in the first half, Arkansas muddled to a 26-point, 35.7-percent shooting effort.

"By the time I came in the game, I could already tell he was frustrated," said Danny Green, who drew the defensive assignment on Weems when Ginyard wasn't in the game. "And that means a lot of people on his team were frustrated, too."

But how did the Tar Heels achieve that frustration?

It was a very, very rare occasion when Weems got the ball at the top of the key and he and Ginyard were matched one-on-one in full view of the 19,477 spectators. That's when everyone notices defense. Most of the work, however, was occurring away from the ball.

On most possessions, Arkansas sent Weems to the corner, around 19 feet from the basket. That's when Ginyard's head began to resemble a Wimbledon spectator taking in a classic McEnroe-Connors match. Back (glancing at Weems) and forth (checking the position of the ball). Back (is he still there?) and forth (do any of my teammates need help defense?).

It was a lot of standing still, watching Weems try to lull him to sleep, followed by a dead sprint around two screens on the opposite side of the court.

That's what happened on the curl move Ginyard mentioned earlier. Weems stood flat-footed for five seconds in the corner. Then, as the shot clock dipped below 10, he sprinted the length of the baseline, trying to use a pair of screens to receive the pass at the top of the key and then knife to the hoop.

The sprint worked. The screens worked. The pass worked. This was probably just like an Arkansas practice, everything running exactly how it was supposed to run.

But Ginyard worked, too. And when Weems caught the ball, the Tar Heel defender beat him to the spot, preventing access to the lane. As soon as he was cut off, Weems immediately gave up the ball, putting his team in the unenviable position of having just three seconds of shot clock time remaining and the ball 22 feet from the basket.

And Ginyard achieved all that havoc without ever making contact.

"When you allow him to get into your body or allow contact, you're allowing him to create separation," Ginyard said. "I want to try to stay off him, but also to be there when he catches the ball."

He was there all night. And in the end, although Weems attempted 20 shots, Ginyard was left to remark, "They really didn't run as many things for him as I thought they would."

Could there be a reason for that, Marcus? Say, the guy wearing the number-one jersey who has now added Weems to a collection of defensive gems that would fill a case in the new basketball museum?

"It could be," Ginyard said with a smile. "But I'm not the guy to answer that."

No need to answer it. For this night, you've already done plenty.

Adam Lucas is the publisher of Tar Heel Monthly. He is also the author or co-author of four books on Carolina basketball.