University of North Carolina Athletics

Extra Points: Road Trip To Atlanta

September 22, 2021 | Football, Featured Writers, Extra Points

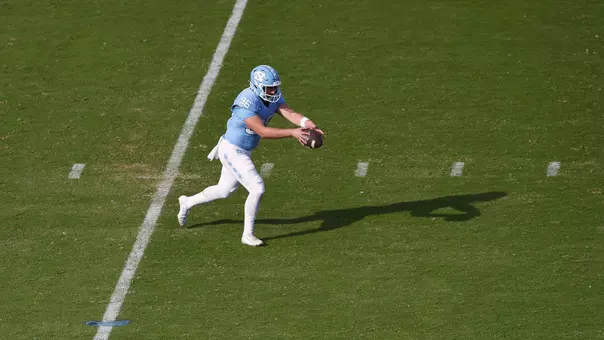

The University of North Carolina football team travels to Atlanta for a football game this weekend, with a traveling party of some 175 people flying by Delta chartered jet, staying in a Marriott hotel and turning the hotel's meeting space into a temporary headquarters to accommodate medical treatment, film study and dinner and breakfast banquets.

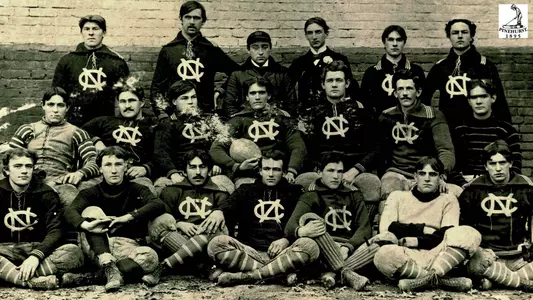

Contrast that to the 1895 Tar Heel team that ventured to Atlanta with three scheduled games in five days in Atlanta, Nashville and Sewanee, and then making a spur-of-the-moment decision to return to Atlanta for a fourth game. A notice in The Tar Heel newspaper (the forerunner to The Daily Tar Heel) said the team would leave Durham at 4 p.m. Friday by train, certainly a long trip for a Saturday afternoon game. The paper in its post-game coverage added, "Our boys had traveled all night getting hardly any sleep and this, together with the fact that several were suffering from previous injuries, must account largely for the poor showing they made."

Carolina was coached that year by Thomas "Doggie" Trenchard, a recent graduate of Princeton who had been named All-America after the 1893 season. Trenchard earned his nickname via his shaggy-haired appearance and would coach the Tar Heels one year and post a 7-1-1 record, then depart to play professionally for a team in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. He later returned to Chapel Hill for a three-year run as coach from 1913-15, including a 10-1 mark in 1914.

The Tar Heels were 2-0 early in the 1895 campaign, dusting off North Carolina A&M 36-0 (the forerunner to N.C. State University) and Richmond 34-0, playing both games in Chapel Hill on the university's original athletic field located on ground just to the east of South Building and the Old Well. That set the squad up for its southern road trip—vs. Georgia in Atlanta on Saturday, October 26, then to Nashville to face Vanderbilt on Monday followed by a quick turnaround against the University of the South in Sewanee on Tuesday.

The city of Atlanta developed an early appetite for football in the late 1800s and brought in teams from Virginia to Alabama for neutral-site games at an athletic field at Piedmont Park, located just east of downtown. The city hosted a "football carnival" during Thanksgiving week in 1892, with a game every day including Carolina vs. Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama (later to become Auburn University) and Virginia vs. Trinity (later to become Duke University). The Tar Heels were scheduled to play Auburn in Atlanta, and then go to Nashville to play Vanderbilt the next day. They handled both opponents easily (64-0 over Auburn and 24-0 over Vanderbilt), and then were invited at the last minute back to Atlanta to play Virginia. The Cavaliers had already won in October, 30-18, so the Tar Heels were motivated for revenge. They accepted the challenge and won the rematch, 26-0.

Georgia in 1895 was in the third year of its football program and was coached by Glenn Warner, who was twenty-four years old and had a law degree from Cornell University. He captained the football team and was the oldest player, so his teammates called him "Pop." He took the coaching job at Georgia when it had 248 students.

The Tar Heel noted that a number of Carolina faculty and students were in attendance, including President George Taylor Winston and associates Charles Baskerville and Edwin Alderman, who were there "enjoying sights with the students." Further, it was an "eager crowd of over a thousand spectators gathered at the athletic park" and added, "As might be expected, the wearers of the Red and Black were in a large majority but when the Carolina Tally-ho drove down the field, followed by the carriage of St. Mary girls, numbers ceased to count."

Carolina won the game 6-0 at a time when a touchdown counted four points and the conversion was two points. The only touchdown came on a play that would later help alter the course of football history—an inadvertent forward pass that was illegal at the time but sparked the imagination of an onlooker to campaign for a much-needed rule change.

George Stephens, the Tar Heels' left halfback, scored on a seventy-yard forward pass from left end Edwin Gregory only five minutes into the game. Warner argued with the referees that the pass was illegal, but none of them got a good look at the pass and allowed the play to stand.

Stephens remembered the play nearly half a century later in a 1940 story in The Asheville Citizen:

"The ball was taken from the center by Joe Whitaker, our quarterback, and given to captain Ed Gregory, who played left end, as he charged through the backfield. As I recall, the play was to go off-tackle. It was permissible in those days to pass the ball behind the line of scrimmage so long as the pass was lateral and not forward.

"Well, we had several plays where the ball carrier would pass to a teammate if he was tackled before he got past the scrimmage line, but I don't recall if this particular play was one of those. Anyway, soon after Gregory received the ball from Whitaker, I remember looking up just as he tossed the ball to me. I was perhaps five yards or more away from him, and I didn't know that it was a forward pass and not lateral. I merely grabbed the ball and ran through a clear field to a touchdown."

John Heisman was the young Auburn coach on the field that day scouting Georgia, an upcoming opponent. Heisman and many others around the sport believed that football was a terrific game but had gotten too violent. The game as it existed in the late 1800s and early 1900s was far beyond anything acceptable in a civilized society. Football was more akin to rugby, and the ball was roughly the size of a small watermelon. Forward passes were not allowed, leading to short lateral tosses, large scrums of players jockeying for the ball and vicious hits. The game rivaled professional baseball in fan appeal, but it was a brutal sport where players locked arms in mass formations and used their heads as battering rams—and this before the advent of the helmet.

Heisman appealed to Walter Camp, the well-established coach deemed in many circles "The Father of Football," and argued that what he had seen from North Carolina that day in Atlanta was the answer to opening the game up and spreading the players out. Camp was a former Yale coach who lost only two games over five seasons in New Haven and now was the coach at Stanford and the head of the football rules committee. Heisman was twenty-six years old and had a more progressive view of football than did Camp, ten years his elder.

Heisman's idea fell on deaf ears, unfortunately. Camp believed the pass would allow luck to play too big a role in the game and lead to quirky plays. He thought the violence was essential to the sport's character, and one of his sympathetic committee members referred to "lightweights" in the discussion of how passing and catching would change the game. Camp thought the pass would make, in essence, for a more "sissified" type of football.

After a series of deaths over the next decade, however, President Theodore Roosevelt summoned leaders of prominent football playing schools to the White House in December 1905 and ordered them to clean their sport up—or he'd see that it was disbanded. Finally, out of that meeting came the legalization of the forward pass.

Meanwhile in Atlanta, the Tar Heels after beating the Bulldogs boarded a train for Nashville and polished off the Commodores of Vanderbilt 12-0, then moved on to Sewanee. Befitting a team that had played two games in three days, the Tar Heels didn't score a point. Fortunately, they didn't allow any, the game ending in a scoreless tie.

"The team arrived at Sewanee Tuesday morning in a condition by no means favorable for playing football; worn out with their long journey and loss of sleep and still feeling the effects of two hard games just played with Georgia and Vanderbilt, they were far from their true form," The Tar Heel reported.

Stephens said the second game with Georgia was the result of a challenge.

"The Carolina alumni gave us a big banquet after the Sewanee game, and while we were there the challenge to play a second game was received from Georgia," he said. "Our money had about run out, and practically all we had was our return train fare. So we figured that we could pick up a few dollars by playing them again, which we did. We thoroughly convinced them that our team was good enough to make it two in a row and that the first victory was no accident."

Four games in seven days? Wow.

"On the way, from Sewanee to Atlanta, Mr. Trenchard worked unceasingly on the players with hot water and liniments," The Tar Heel reported. "The result was that we went into the second Georgia game in much better trim than the Sewanee game and the result proved that we were superior to Georgia without any doubt."

Carolina beat Georgia again, this time by a 10-6 score. The Tar Heel said the game was played amid lots of mud and a "mean rain fell during the entire game."

"In its recent trip the team has done itself proud, deserves the hearty congratulations of the student body, and gave away the secret that the Southern Football Championship will soon be ours," The Tar Heel observed.

Carolina finished the year 7-1-1 and outscored its opponents 146-17 in posting its best record in its eighth year of football.

"At every place they have visited they have won admiration for their behavior and without doubt made many new friends for Carolina," The Tar Heel said. "And this pride comes too from the great increase of 'college spirit' which our new growth in athletics and in every other branch of University life has instilled into us."

Imagine the equivalent today—Carolina plays Georgia Tech on Saturday, goes to Knoxville to play Tennessee on Monday, a quick turnaround at Vanderbilt on Tuesday, then back to Atlanta for a rematch with the Yellow Jackets on Thursday.

Lee Pace has written extensively about that "first forward pass" and its aftermath in his book "First Pass—The Day College Football Charted a New Course." Write him at leepace7@gmail.com and following him @LeePaceTweet.

Contrast that to the 1895 Tar Heel team that ventured to Atlanta with three scheduled games in five days in Atlanta, Nashville and Sewanee, and then making a spur-of-the-moment decision to return to Atlanta for a fourth game. A notice in The Tar Heel newspaper (the forerunner to The Daily Tar Heel) said the team would leave Durham at 4 p.m. Friday by train, certainly a long trip for a Saturday afternoon game. The paper in its post-game coverage added, "Our boys had traveled all night getting hardly any sleep and this, together with the fact that several were suffering from previous injuries, must account largely for the poor showing they made."

Carolina was coached that year by Thomas "Doggie" Trenchard, a recent graduate of Princeton who had been named All-America after the 1893 season. Trenchard earned his nickname via his shaggy-haired appearance and would coach the Tar Heels one year and post a 7-1-1 record, then depart to play professionally for a team in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. He later returned to Chapel Hill for a three-year run as coach from 1913-15, including a 10-1 mark in 1914.

The Tar Heels were 2-0 early in the 1895 campaign, dusting off North Carolina A&M 36-0 (the forerunner to N.C. State University) and Richmond 34-0, playing both games in Chapel Hill on the university's original athletic field located on ground just to the east of South Building and the Old Well. That set the squad up for its southern road trip—vs. Georgia in Atlanta on Saturday, October 26, then to Nashville to face Vanderbilt on Monday followed by a quick turnaround against the University of the South in Sewanee on Tuesday.

The city of Atlanta developed an early appetite for football in the late 1800s and brought in teams from Virginia to Alabama for neutral-site games at an athletic field at Piedmont Park, located just east of downtown. The city hosted a "football carnival" during Thanksgiving week in 1892, with a game every day including Carolina vs. Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama (later to become Auburn University) and Virginia vs. Trinity (later to become Duke University). The Tar Heels were scheduled to play Auburn in Atlanta, and then go to Nashville to play Vanderbilt the next day. They handled both opponents easily (64-0 over Auburn and 24-0 over Vanderbilt), and then were invited at the last minute back to Atlanta to play Virginia. The Cavaliers had already won in October, 30-18, so the Tar Heels were motivated for revenge. They accepted the challenge and won the rematch, 26-0.

Georgia in 1895 was in the third year of its football program and was coached by Glenn Warner, who was twenty-four years old and had a law degree from Cornell University. He captained the football team and was the oldest player, so his teammates called him "Pop." He took the coaching job at Georgia when it had 248 students.

The Tar Heel noted that a number of Carolina faculty and students were in attendance, including President George Taylor Winston and associates Charles Baskerville and Edwin Alderman, who were there "enjoying sights with the students." Further, it was an "eager crowd of over a thousand spectators gathered at the athletic park" and added, "As might be expected, the wearers of the Red and Black were in a large majority but when the Carolina Tally-ho drove down the field, followed by the carriage of St. Mary girls, numbers ceased to count."

Carolina won the game 6-0 at a time when a touchdown counted four points and the conversion was two points. The only touchdown came on a play that would later help alter the course of football history—an inadvertent forward pass that was illegal at the time but sparked the imagination of an onlooker to campaign for a much-needed rule change.

George Stephens, the Tar Heels' left halfback, scored on a seventy-yard forward pass from left end Edwin Gregory only five minutes into the game. Warner argued with the referees that the pass was illegal, but none of them got a good look at the pass and allowed the play to stand.

Stephens remembered the play nearly half a century later in a 1940 story in The Asheville Citizen:

"The ball was taken from the center by Joe Whitaker, our quarterback, and given to captain Ed Gregory, who played left end, as he charged through the backfield. As I recall, the play was to go off-tackle. It was permissible in those days to pass the ball behind the line of scrimmage so long as the pass was lateral and not forward.

"Well, we had several plays where the ball carrier would pass to a teammate if he was tackled before he got past the scrimmage line, but I don't recall if this particular play was one of those. Anyway, soon after Gregory received the ball from Whitaker, I remember looking up just as he tossed the ball to me. I was perhaps five yards or more away from him, and I didn't know that it was a forward pass and not lateral. I merely grabbed the ball and ran through a clear field to a touchdown."

John Heisman was the young Auburn coach on the field that day scouting Georgia, an upcoming opponent. Heisman and many others around the sport believed that football was a terrific game but had gotten too violent. The game as it existed in the late 1800s and early 1900s was far beyond anything acceptable in a civilized society. Football was more akin to rugby, and the ball was roughly the size of a small watermelon. Forward passes were not allowed, leading to short lateral tosses, large scrums of players jockeying for the ball and vicious hits. The game rivaled professional baseball in fan appeal, but it was a brutal sport where players locked arms in mass formations and used their heads as battering rams—and this before the advent of the helmet.

Heisman appealed to Walter Camp, the well-established coach deemed in many circles "The Father of Football," and argued that what he had seen from North Carolina that day in Atlanta was the answer to opening the game up and spreading the players out. Camp was a former Yale coach who lost only two games over five seasons in New Haven and now was the coach at Stanford and the head of the football rules committee. Heisman was twenty-six years old and had a more progressive view of football than did Camp, ten years his elder.

Heisman's idea fell on deaf ears, unfortunately. Camp believed the pass would allow luck to play too big a role in the game and lead to quirky plays. He thought the violence was essential to the sport's character, and one of his sympathetic committee members referred to "lightweights" in the discussion of how passing and catching would change the game. Camp thought the pass would make, in essence, for a more "sissified" type of football.

After a series of deaths over the next decade, however, President Theodore Roosevelt summoned leaders of prominent football playing schools to the White House in December 1905 and ordered them to clean their sport up—or he'd see that it was disbanded. Finally, out of that meeting came the legalization of the forward pass.

Meanwhile in Atlanta, the Tar Heels after beating the Bulldogs boarded a train for Nashville and polished off the Commodores of Vanderbilt 12-0, then moved on to Sewanee. Befitting a team that had played two games in three days, the Tar Heels didn't score a point. Fortunately, they didn't allow any, the game ending in a scoreless tie.

"The team arrived at Sewanee Tuesday morning in a condition by no means favorable for playing football; worn out with their long journey and loss of sleep and still feeling the effects of two hard games just played with Georgia and Vanderbilt, they were far from their true form," The Tar Heel reported.

Stephens said the second game with Georgia was the result of a challenge.

"The Carolina alumni gave us a big banquet after the Sewanee game, and while we were there the challenge to play a second game was received from Georgia," he said. "Our money had about run out, and practically all we had was our return train fare. So we figured that we could pick up a few dollars by playing them again, which we did. We thoroughly convinced them that our team was good enough to make it two in a row and that the first victory was no accident."

Four games in seven days? Wow.

"On the way, from Sewanee to Atlanta, Mr. Trenchard worked unceasingly on the players with hot water and liniments," The Tar Heel reported. "The result was that we went into the second Georgia game in much better trim than the Sewanee game and the result proved that we were superior to Georgia without any doubt."

Carolina beat Georgia again, this time by a 10-6 score. The Tar Heel said the game was played amid lots of mud and a "mean rain fell during the entire game."

"In its recent trip the team has done itself proud, deserves the hearty congratulations of the student body, and gave away the secret that the Southern Football Championship will soon be ours," The Tar Heel observed.

Carolina finished the year 7-1-1 and outscored its opponents 146-17 in posting its best record in its eighth year of football.

"At every place they have visited they have won admiration for their behavior and without doubt made many new friends for Carolina," The Tar Heel said. "And this pride comes too from the great increase of 'college spirit' which our new growth in athletics and in every other branch of University life has instilled into us."

Imagine the equivalent today—Carolina plays Georgia Tech on Saturday, goes to Knoxville to play Tennessee on Monday, a quick turnaround at Vanderbilt on Tuesday, then back to Atlanta for a rematch with the Yellow Jackets on Thursday.

Lee Pace has written extensively about that "first forward pass" and its aftermath in his book "First Pass—The Day College Football Charted a New Course." Write him at leepace7@gmail.com and following him @LeePaceTweet.

Hubert West: 2026 Tar Heel Trailblazer

Wednesday, February 18

UNC Baseball: Tar Heels Shut Down Richmond, 10-0

Wednesday, February 18

WBB: Post-Duke Conference - Feb. 15, 2026

Sunday, February 15

UNC Women's Basketball: Tar Heels Fall at Duke, 72-68

Sunday, February 15