University of North Carolina Athletics

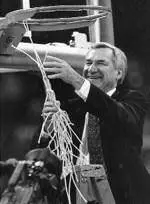

Smith's First Five Teams To Reunite Tonight

December 19, 2002 | Men's Basketball

Dec. 19, 2002

By Adam Lucas

For two days this week, a group of former Tar Heels will recreate Camelot.

Approximately three-quarters of the lettermen from Dean Smith's first five teams (1961-66) will gather in Chapel Hill on December 18 and 19. It marks the first time that the players from those historic teams have been together as a group since the dedication of the Smith Center in 1986.

"It was a different era, both with basketball and in America," says Mike Cooke, who averaged 7.6 points per game during his three-year (freshmen were not eligible to play during Smith's early years) Tar Heel career. "It was the time of Camelot."

The first five teams of Smith's tenure are often treated by fans and historians as stepchildren to the three consecutive Final Four teams that would follow from 1967-69. But in retrospect, they were victims of circumstances more than ineffectual play. In those days, only the ACC Tournament champion made the NCAA Tournament. Had today's rules been in place, it's entirely possible that the Tar Heels would have made the postseason in three of Smith's first five years.

In addition, while it may have been Camelot in the nation's capital, things weren't quite so serene in Chapel Hill. Following an investigation into recruiting violations, the Tar Heels were hit with limited NCAA sanctions in 1960. To make matters worse, a gambling scandal tainted Carolina and NC State one year later, and the university self-imposed several limitations, including a restricted regular-season schedule and severe recruiting handicaps.

That explains why when Chancellor Bill Aycock began looking for a new basketball coach to replace the departing Frank McGuire in the spring of 1961, he was looking for more than just a hardwood strategist; he was also searching for someone who would be a qualified caretaker of the program.

Enter a young man who, by today's standards, might have caused a firestorm of controversy among fans. Thirty-year-old Dean Edwards Smith had never been a head coach at another Division I school, did not attend Carolina as an undergraduate, and had only limited playing experience, although he was on the roster of the 1952 national champion Kansas Jayhawks team. Smith had come to Chapel Hill just three years earlier, signing up to become McGuire's top assistant.

The pair worked well together, with Smith, who had spent two seasons at the Air Force Academy, often serving as the regimented disciplinarian to McGuire's more laid-back style.

"He was a stickler," Cooke says. "The last Dixie Classic was my freshman year. It was a big event, and I had gotten a brand new sweater for Christmas, and that was a big deal. The freshman team had tickets to sit in the stands for the Dixie Classic, and I was all decked out in my new sweater. When we came back to school, Coach Smith passed me at the gym and said, 'I saw you at the Dixie Classic. You didn't have a coat and tie on. Don't let me ever see you without a coat and tie on.'"

Despite the occasionally stringent rules, it didn't take Smith long to impress his players with his intense practice organization. Although the coach's desk was legendarily messy, he was exceptionally detailed for the hours spent on the court each day. Peppy Callahan, who was the captain of Smith's first varsity team, also played on the new coach's first freshman team during the 1957-58 season.

"He was very organized," Callahan says. "He had a very analytical mind and he knew how to break things down."

"I'm not very organized in my life, except when it's time for practice," Smith says. "We had good practice sessions."

Quality practice time was a necessity in Smith's first season, 1961-62, because the Tar Heels played a very difficult schedule. NC State coach Everett Case had already advised the rookie Carolina coach that Duke and Wake Forest would be eager to capitalize on the misfortunes of their in-state brethren brought on by the gambling sanctions.

The new scheduling restrictions mandated that Carolina could keep only two of the games against non-ACC opponents that had already been scheduled. Given a choice about which games to keep, Smith followed a policy that would later serve him well-he kept the toughest two games, Notre Dame and Indiana, on the schedule. At the time, it seemed like a hearty move. In retrospect, the head coach can laugh about it.

"It just means that I was dumb enough to keep the two toughest games on the schedule," Smith says with a smile.

His first Carolina team finished 8-9, including a win over the Fighting Irish. But it wasn't until the next season, when the Tar Heels toppled mighty Kentucky in Lexington, that word began to leak out about something special happening in Chapel Hill. The 1962-63 season was Billy Cunningham's first with the varsity, and point guard Larry Brown was coming off a solid year.

Carolina lost to Indiana 90-76 in Bloomington on a December Saturday and traveled to Lexington two days later to play the highly-ranked Wildcats. Coming off a 14-point loss and playing a UK squad that lost at home about as often as the Kentucky Derby wasn't a sellout, there was little reason to suspect an upset. But a strategic twist provided a spark that led to a 68-66 Tar Heel win. Smith had 6-foot-1 Yogi Poteet match up man-to-man with Kentucky's All-American scorer, Cotton Nash. The other four defenders played a point zone, creating one of the first examples of an effective box-in-one defense.

"When Coach Smith designed that gameplan with the box-in-one against Cotton Nash, you could see he had the capability to be a great coach," Callahan says. "You knew that when he started bringing in the players, it could be special."

ut before basketball would become special again in Chapel Hill, Smith and his Tar Heels had to endure a trying 1963-64 season. With the return of Cunningham, expectations were high. Carolina had finished 10-4 in the ACC the previous year, and an early four-game winning streak looked promising. The momentum changed after that short hot streak, however, and Smith would learn one of his most enduring coaching principles: teams, not individual players, win games.

"I did a lousy job in my third year," Smith says. "I tried different combinations and was really disappointed. I wanted Billy to do everything. I thought we could throw the ball to Billy and he could bring the ball up against the press and do it all. We were team-oriented in our first two seasons, but I kind of lost sight of that by trying to use Billy so much."

After that season ended with a disappointing 12-12 overall record, Smith would never again allow an individual to dictate the play of the team. The next year, 1964-65, is one of the most famous in Carolina basketball history-but not for a positive reason.

It was upon returning from a road trip that season to Wake Forest, a 107-85 defeat that was Carolina's fourth straight loss, that a group of Carolina students hung Smith in effigy. The fourth-year head coach paid little attention to the display-he was more concerned with preparing his team to play Duke. Cunningham and Billy Galantai bounded off the bus to take down the effigy.

"You never hear of anyone getting hung in effigy today," Smith says. "They just fire them. As a coach, you just want to know that your players are with you, and I knew that they were. I also knew Chancellor Aycock was with me. I wasn't oblivious to what was going on. People weren't happy, and we weren't happy either. We had played only two games in Chapel Hill [the Tar Heels would play only seven home games all year]. I almost scheduled myself out of a job."

Although there was another less well-known effigy incident later that season, there were also signs that the fortunes of Carolina basketball were beginning to turn around. After some initial missteps on the recruiting trail, Smith landed his first big-name recruit when Bob Lewis committed in 1963. One year later, the Tar Heels won an epic recruiting battle with Duke for Larry Miller. Those players would eventually be known as the "L&M Boys," the foundation of Smith's first Final Four team in 1967. The tandem first paired up during the 1965-66 season, a year that ended just one point shy of the ACC Tournament championship game.

Smith made use of his talented duo by implementing the Four Corners in an early-season win at Ohio State. It was pressed into use again in the ACC semifinals against Duke, a game that stood 7-5 at halftime and was eventually won 21-20 by the Blue Devils.

So ended the first half a decade of Smith's eventual 36-year tenure as the head of the Tar Heels. With the exciting, high-scoring Miller and Lewis returning, there were already signs of the basketball prowess that was to come. Carolina compiled a 41-29 Atlantic Coast Conference record in those initial seasons, three games better than NC State, which suffered under similar restrictions but had the established Everett Case as head coach.

"It means a lot to Carolina basketball that the former players want to come back," says head coach Matt Doherty, who stopped by the team's gathering on Wednesday night. "They mean a lot to Carolina basketball and we appreciate what they have done for the program."

In addition to their on-court success, the players who will gather in Chapel Hill this week also revealed a trait that was to become commonplace in Carolina basketball: they were solid, well-rounded citizens. One hundred percent of them received their undergraduate degrees, and an astounding 68 percent of those players went on to obtain graduate degrees. Earl Johnson, Richard Vinroot, and Charlie Shaffer were class presidents. Although Smith claims he doesn't remember particularly argumentative practices, nearly a fifth of the players on those teams became lawyers.

Those 40 players who lettered in those first five years went on to touch almost every segment of the business world. Ironically, it is mostly those who pursued a career in the sports field-Larry Brown as the current head coach of the Philadelphia 76ers and Donnie Walsh with the Indiana Pacers-who are unable to return to their alma mater for the two-day reunion.

"They were great student-athletes and great for the program," Smith says. "I know I was a better coach in 1997 than I was in 1962, but the players responded very well."

Adam Lucas is the publisher of Tar Heel Monthly and can be reached at alucas@tarheelmonthly.com. To subscribe to Tar Heel Monthly, click here.