University of North Carolina Athletics

Remembering: A Look Back at Nov. 22, 1963

November 21, 2003 | Football

Nov. 21, 2003

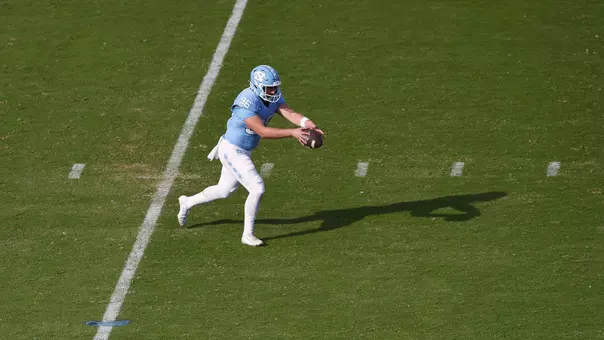

In 1963, the Tar Heel football team was 7-2 approaching the Duke game, scheduled for November 23. However, the tragic events of November 22 in Dallas, Texas, shattered the American landscape and forever altered how people remembered that weekend. Roger Smith, wingback and co-captain of the Tar Heels, is now one of the pre-eminent attorneys in the state of North Carolina. On the 40th anniversary of President Kennedy's death, we are fortunate to have Mr. Smith's recollections of one of the most remarkable moments in American history.

By Roger Smith, 1963 Carolina football team

y late November 1963, the maple trees lining the boundary between Navy Field and the elevated intramural fields, along South Road next to Woollen Gym, had nearly completed their annual run through the colors and gone to rest. As football players had done in seasons past, we members of the 1963 team had marked the passage of the season by the changes in the foliage of those trees: clover green during the sweltering two-a-days and early September openers -- a win over Virginia, a loss at Michigan State; straw yellow in early October -- wins at Wake Forest and Maryland; old gold in late October -- wins over North Carolina State and South Carolina; apple russet through early November -- a win over Georgia, a loss to Clemson and a win over Miami.

Now, in the afterglow of the November 16 Miami victory, and with the tips of the maple leaves edging toward brown, Coach Jim Hickey announced an extraordinary challenge: "Men," he said, "Beat Duke in Wallace Wade Stadium on Saturday and you will be invited to play in the Gator Bowl." The team voted, with great enthusiasm and near unanimity, to accept such an invitation if it were extended. The lone dissenter was Max Chapman, the team's place-kicker, who explained that he had not seen his girlfriend since August, and wanted to go home for the holidays.

Duke week practices were serious and spirited. The offense concentrated on what it had done so successfully all season. Quarterback Junior Edge would give the ball to Ken Willard until the defense stopped him, then throw 10-yard down-and-outs to Bob Lacey along the sidelines until the defense stopped him, then give the ball back to Willard until he was stopped, then pass again to Lacey until he was stopped, and so on down the field to the end zone.

Friday, November 22, was crisp and clear as I left the white frame house at 509 Pritchard Avenue, where I lived with my wife, Bonnie, and our baby daughter, Kim, and headed to Kenan Stadium to begin the butterfly-filled pre-game routine. We would dress out light, meet and discuss the game plan, loosen up, walk through the offense, go to a movie, spend the night in a hotel, and travel by bus to Durham on Saturday.

As was my pattern on such days, I would walk down Pritchard to Rosemary, turn left on Rosemary, right on Columbia, left onto Franklin, enter campus at Silent Sam, cross Cameron Avenue at the Old Well to Gerrard Hall and Y Court, descend the steps in front of South Building, pass to the east of Hanes and Gardner Halls and to the west of Wilson Library, cross South Road to the brick walkways at the base of the bell tower, and follow the well-worn path through Kenan Woods to the Field House.

On this day, something was noticeably out of rhyme: by the time I reached South Building, I could hear the bell tower chiming hymns. The bells never played at this time of day. When I reached the bell tower itself, I encountered a young woman in tears, looking lost. "What's wrong?," I asked her. "President Kennedy has been shot," she said.

I walked hurriedly on the needle-strewn path through the pines of Kenan Woods, breathing the musty aroma of the slow-burn from the forest floor, passed the North Gate, descended the last sharp hill by the rock wall, and entered the field house. By then, we all had heard the news. We dressed out in silence and went to the meeting room. Coach Hickey and the other coaches entered together. Coach Hickey sat down facing us in a backward gray metal folding chair, his knees on either side of the back rest. He leaned forward, and said, "Men, the President has been shot and killed. We won't be playing Duke tomorrow. With the President having been killed, we come to understand clearly that football is just a game. Go back downstairs, get dressed, and go your separate ways to grieve. I'll see you back here on Monday." I went home.

I spent the weekend with Bonnie and Kim in front of the television set, mesmerized by the scenes and words: Dallas; assassination; Dealey Plaza; Parkland Hospital; the Texas School Book Depository; the Sixth Floor; three cartridges; the Manlicher-Carcano rifle; the grassy knoll; Officer J.D. Tippit; Lee Harvey Oswald; Ms. Kennedy's stained pink dress and crumpled red roses; President Lyndon Baines Johnson; Jack Ruby.

The funeral began at 10:00 A.M. on Monday, November 25, a brilliantly clear and bitterly cold day in Washington and Chapel Hill. At our house on Pritchard Avenue, as the world outside stood still, we watched it all on television: the brave, dignified family; the cortege; the horse-drawn caisson carrying the flag-draped brass casket; the prancing horse with no rider; John-John's salute; Arlington National Cemetery; the eternal flame; twenty-one gun salute; three musket volleys; Taps. I held baby Kim on my lap, bouncing her gently to the steady beat of the processional drums, and whispering that I would tell her all about this time some day.

In the afternoon, after the funeral, the team met back at Kenan Field House. The Duke game had been rescheduled for Thanksgiving Day, Thursday, November 28. The short week passed quickly. On Thanksgiving Day, at Wallace Wade Stadium, Carolina and Duke played to nearly a dead heat. As the fourth quarter wound down, Duke led 14 to 13, and the Gator Bowl dream was slipping away. On our last possession, with time running out, we drove the ball into Duke territory at the open end of the Stadium. There, on fourth-and-long, Max Chapman calmly trotted onto the field to attempt a field goal.

The snap was good, the spot was good, and Max stepped toward the ball. If he made it, we were off to the Gator Bowl; if he missed it, Max was off to home for the holidays with his girlfriend. As everyone stood in frozen silence, the ball sailed off Max's foot and, flying straight and low, it cleared the crossbar by inches. Carolina 16, Duke 14.

y the time we left for Jacksonville, the limbs of the maple trees hung bare over sweeps of scattered brown leaves. The team arrived in Florida before Christmas, stayed at the historic and luxurious Ponce de Leon Hotel, practiced gently once a day, saw the sights, gathered around an evergreen tree on Christmas morning, played among the swaying palms, and stayed out much too late every night. After all, we reminded ourselves each evening, Coach Hickey had said, "Men, we're going down there to win a game, but the trip is a reward for the season; just go and have fun." He kept his word: no curfew, no bed checks, no questions.

On game day, December 28, with the team feeling loose and almost giddy, and before a capacity crowd that included Max Chapman's girlfriend, Carolina won its first bowl championship, a 35-0 victory over the Air Force Academy in the Gator Bowl. Every member of the team played.

On the weekend of October 3, 2003, as the Navy Field trees were off on their annual run through the colors, the Team of '63 gathered in Chapel Hill to celebrate the 40th Anniversary of its Gator Bowl Championship. At the Friday night dinner, nearly every member of the team rose to speak. The room echoed with pride in what we accomplished back then, and far greater pride in what we had accomplished since.

For those of us who were alive at the time, the death of President Kennedy in Dallas on Friday, November 22, 1963, seemed to change nearly everything: the University, the State, the Nation, the world, and the course of history. We lost our individual and collective innocence and gained furrowed brows. Yet, through the days of change that followed the President's death, coaches and players on the Team of '63 acquired, at the core of their beings, an abiding appreciation for things that never change: the Navy Field trees always come back to green.