University of North Carolina Athletics

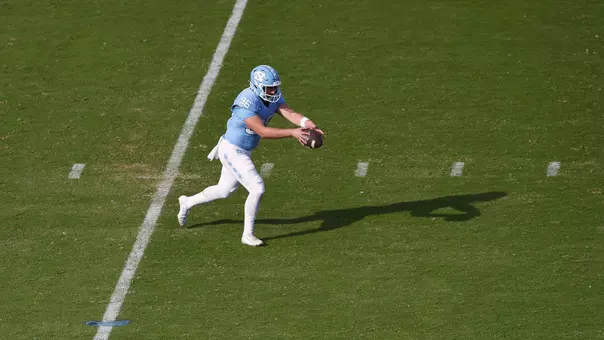

Photo by: Jeffrey A. Camarati

Extra Points: The Difference

April 10, 2019 | Football, Featured Writers, Extra Points

By Lee Pace

Jay Bateman looks back on his years in the 1980s growing up in the Richmond suburb of Glen Allen and lists the things he wasn't very good at: "Couldn't hit a curve ball. Didn't run very fast. Couldn't shoot 3-pointers. I was 5-9 on a good day, so I couldn't go down in the box in basketball," he says.

The position of linebacker on the football field, however, provided a haven for a kid with some brains and guts and a lot of drive. By the time he graduated from Hermitage High in 1991, he led a team in tackles that had three future NFL guys on its roster, one of them a linebacker named Jamie Sharper, who'd go on to a productive career at Virginia and then a decade with three teams in the NFL.

"One value in the game of football I don't think exists in any other sport is toughness and work ethic," Bateman says. "I was never going to be big enough to be a lineman, not fast enough to be a running back. So they moved me to linebacker. That's kinda what you do with sawed-off guys who are tough in high school. I was always attracted to the tough guys, the defensive guys. Those were the guys I was drawn to. I wasn't as much into the quarterbacks and the pretty running backs."

Therein lays the essence of Carolina's first-year safeties coach and co-defensive coordinator.

"You could say I enjoy being around tough, cerebral people," Bateman says. "I tell our guys all the time, 'Smart guys beat dumb guys in all walks of life.' I like to be around smart kids. And we have really smart kids here."

Bateman and his fellow defensive coaches face a formidable task in seeking to field a quality unit given the loss of four key linemen from 2018, offseason injuries that have sidelined a half dozen potential contributors this spring and the attrition of one player to offense and another to a transfer. Mack Brown has consistently mentioned that depth in the front seven is his biggest worry entering the 2019 season. So as the defensive staff waits to get players back from injury and busts its collective tail to restock the personnel cupboard via recruiting, Bateman is busy establishing his thumbprint on the unit.

"I'm extremely happy with these players," Bateman says. "They have been so open, so accepting to trying something new. Some have had three or four different position coaches, which is a real shame. These are really, really good kids, which is a tribute to Coach [Larry] Fedora. We've just got to get a little healthier and play better. I feel like, man, I have to do everything in my power to give them a chance to win a game."

Bateman's story at Carolina has many elements. One is a mindset and emphasis on block-destruction and tackling, the latter executed with a technique he imported from Seattle of the NFL to his previous coaching stop at Army West Point to reduce injuries. Another is a schematic mindset that is aggressive and attempts to lay as much wood to modern offenses as the offenses create with tempo and stretching the field. Read and react? Hardly. It's more like search and destroy.

After his first year at Army in 2014 when the Black Knights were No. 90 nationally in total defense and at the beginning of building what would become a rock-solid program under Coach Jeff Monken, the light popped on for an initiative he wanted to implement at West Point the next year—five minutes of carefully choreographed, intense and fast-paced drills on shucking blocks and taking ball-carriers to the ground. It would fall in period one every practice, before players got tired.

He themed the regimen, "The Difference."

"I got to thinking about it and said, 'You know what, if we tackle really well and we get off blocks really well, the rest of it doesn't matter,'" he says. "You've got to whip blocks and got to tackle really well. I feel like you get what you emphasize. This would be what would make us different from every other defense in the country. We're going to be the best tacklers and be the hardest to block."

Over the next four seasons, Army would be among the nation's leaders defensively and rank No. 4 in total defense in 2016 and No. 8 last fall, both years allowing under 300 yards a game.

"If you watch our film at Army, you'll see kids who are really hard to block, and are really good tacklers," Bateman says. "When I got here and I watched the film, the thing I knew I could improve was our angles to the football, our tackling and our block destruction. If you don't improve those, the rest of it doesn't matter anyway. I want us to be known as a violent tackling team. It's starting to show up, we'll keep banging at it. When it flips, you can tell because you suck the air out of the running game."

A second watershed decision further built the Black Knights' defensive tradition—that of overhauling the team's tackling technique. Army's defense had 14 games total missed by various players because of concussions in 2014. Bateman watched Seattle Seahawks games and read about Coach Pete Carroll's tackling philosophy. Carroll and assistant Rocky Seto were eschewing the age-old tackling dictums of planting your face mask in a runner's numbers if you were hitting him head-on or at least having your head on the upfield side of the runner if approaching from an angle. The Seahawks were using what they called the "Hawk" technique of attacking the runner's thighs with the defender's nearest shoulder, wrapping his legs with both arms and driving or rolling the runner to the ground. The technique is more popularly known as the "rugby" tackle because it's the method preferred by rugby players, who never wear helmets and need to keep their heads out of harm's way.

Bateman and his staff learned the rugby tackle and taught it to their players going into the 2015 season.

"The next year, we had one player miss a game with a head injury," Bateman says. "That's huge. There were always some things about tackling as it had been taught forever that didn't make sense to me. I'm supposed to run inside-out on the ball and then get my head across. That's physically impossible. That always caused me conflict. The game of football was so under attack, as a coach if you don't do something different, you're sticking your head in the sand. The last couple of years at Army, one or two kids missed one game for concussions and we're playing at a higher level and playing against better opponents. You say, 'Gosh, this has got to be a piece of it.'"

So far through spring practice, the Tar Heels think these coaching initiatives will pay off come Saturdays in the fall.

"I think [the 'Difference' period] has a great impact on the team," outside linebacker Tomon Fox says. "These drills help us finish, remind us of the importance of shedding blocks. We do them at the start every day, and once you get it in your head, it's going to make you do all those things in team periods, individual periods."

"Coach Bateman is tough and smart," safety Trey Morrison adds. "He's real hard on us, he wants everything perfect. I think we're making tackles in open space better. We're leveraging the ball, taking the proper angles, tracking the back hip. Every day, we're making progress. I think by next fall, we'll be really good."

It's only after emphasizing the importance of warding off blocks and taking runners to the ground with precision that Bateman even broaches the subject of scheme, and even then he says that identifying the Tar Heels' base as a "3-4" is almost superfluous.

"Scheme is a really over-rated thing," he says. "If our scheme is not multiple enough to put our best 11 on the field, then I should be fired. People say, 'Are you 3-4?' I say, 'Yeah, sure, we're 3-4, but we line up in everything.' It just depends on what's our best call and who are we playing? Last year, we were in two-down more than anything."

To wit, in the Tar Heels' scrimmage last Saturday, the first 10 defensive snaps showed Bateman using six different fronts (and only on two snaps were the Tar Heels in their "base" alignment). They played nine coverages and brought four different blitzes. What Bateman will say, though, is that the Tar Heels not play defense in a "Tampa 2" mode of having two deep safeties, playing lots of zone, trying to generate heat with four down linemen and keeping everything underneath.

"If you're just dropping in what I call 'vision coverage' where I'm seeing the ball and I'm breaking, you used to be able do that and be pretty good," he says. "The Tampa Bay Buccaneers won a Super Bowl doing that. Today, though, the ball comes out so fast and quarterbacks are so accurate and receivers are so good in space. You go tackle it and say you did a good job and you're second-and-four. I'm not great at math, but I know if they're doing that every time, they're going to get a first down.

"Our defense will be like rebel warriors, we kind of come from everywhere and we try to bait you into things, cause confusion, cause havoc, infiltrate from within. You try to create negative plays, you try to create incompletions, you try to create sacks. If you do that, you're in pretty good shape."

And the first rule: Everyone is a blitzer.

"I love it," says Morrison, a nickel back. "We can come from anywhere on the field. I've lined up everywhere this spring."

"I love being with coordinators who think 'attack,'" adds cornerbacks coach Dré Bly. "That's what Jay did at Army and that's what made him successful. We have a variety of looks and bring guys from all over the field. Our guys are embracing the moment and excited about this new opportunity."

One visitor to practice in early March was Sharper, who's now coaching at Georgetown University. He noted that Bateman's "fiery personality" had not dissipated in two decades and was amused to see Bateman nod toward Sharper and joke with his players that ex-NFL guys had nothing on him in high school.

"Then he was showing tackling technique and instead of talking about it, he rolled into Dré Bly and took him to the ground," Sharper says. "He's still got that energy, he's still throwing his body around and tackling another coach. He's definitely bringing the pressure. Those kids will enjoy bringing that pressure."

Chapel Hill writer Lee Pace has been covering Tar Heel football with his "Extra Points" column since 1990 and in 2016 published the definitive history of Kenan Stadium, "Football in a Forest." Follow him @LeePaceTweet and write him at leepace7@gmail.com

Jay Bateman looks back on his years in the 1980s growing up in the Richmond suburb of Glen Allen and lists the things he wasn't very good at: "Couldn't hit a curve ball. Didn't run very fast. Couldn't shoot 3-pointers. I was 5-9 on a good day, so I couldn't go down in the box in basketball," he says.

The position of linebacker on the football field, however, provided a haven for a kid with some brains and guts and a lot of drive. By the time he graduated from Hermitage High in 1991, he led a team in tackles that had three future NFL guys on its roster, one of them a linebacker named Jamie Sharper, who'd go on to a productive career at Virginia and then a decade with three teams in the NFL.

"One value in the game of football I don't think exists in any other sport is toughness and work ethic," Bateman says. "I was never going to be big enough to be a lineman, not fast enough to be a running back. So they moved me to linebacker. That's kinda what you do with sawed-off guys who are tough in high school. I was always attracted to the tough guys, the defensive guys. Those were the guys I was drawn to. I wasn't as much into the quarterbacks and the pretty running backs."

Therein lays the essence of Carolina's first-year safeties coach and co-defensive coordinator.

"You could say I enjoy being around tough, cerebral people," Bateman says. "I tell our guys all the time, 'Smart guys beat dumb guys in all walks of life.' I like to be around smart kids. And we have really smart kids here."

Bateman and his fellow defensive coaches face a formidable task in seeking to field a quality unit given the loss of four key linemen from 2018, offseason injuries that have sidelined a half dozen potential contributors this spring and the attrition of one player to offense and another to a transfer. Mack Brown has consistently mentioned that depth in the front seven is his biggest worry entering the 2019 season. So as the defensive staff waits to get players back from injury and busts its collective tail to restock the personnel cupboard via recruiting, Bateman is busy establishing his thumbprint on the unit.

"I'm extremely happy with these players," Bateman says. "They have been so open, so accepting to trying something new. Some have had three or four different position coaches, which is a real shame. These are really, really good kids, which is a tribute to Coach [Larry] Fedora. We've just got to get a little healthier and play better. I feel like, man, I have to do everything in my power to give them a chance to win a game."

Bateman's story at Carolina has many elements. One is a mindset and emphasis on block-destruction and tackling, the latter executed with a technique he imported from Seattle of the NFL to his previous coaching stop at Army West Point to reduce injuries. Another is a schematic mindset that is aggressive and attempts to lay as much wood to modern offenses as the offenses create with tempo and stretching the field. Read and react? Hardly. It's more like search and destroy.

After his first year at Army in 2014 when the Black Knights were No. 90 nationally in total defense and at the beginning of building what would become a rock-solid program under Coach Jeff Monken, the light popped on for an initiative he wanted to implement at West Point the next year—five minutes of carefully choreographed, intense and fast-paced drills on shucking blocks and taking ball-carriers to the ground. It would fall in period one every practice, before players got tired.

He themed the regimen, "The Difference."

"I got to thinking about it and said, 'You know what, if we tackle really well and we get off blocks really well, the rest of it doesn't matter,'" he says. "You've got to whip blocks and got to tackle really well. I feel like you get what you emphasize. This would be what would make us different from every other defense in the country. We're going to be the best tacklers and be the hardest to block."

Over the next four seasons, Army would be among the nation's leaders defensively and rank No. 4 in total defense in 2016 and No. 8 last fall, both years allowing under 300 yards a game.

"If you watch our film at Army, you'll see kids who are really hard to block, and are really good tacklers," Bateman says. "When I got here and I watched the film, the thing I knew I could improve was our angles to the football, our tackling and our block destruction. If you don't improve those, the rest of it doesn't matter anyway. I want us to be known as a violent tackling team. It's starting to show up, we'll keep banging at it. When it flips, you can tell because you suck the air out of the running game."

A second watershed decision further built the Black Knights' defensive tradition—that of overhauling the team's tackling technique. Army's defense had 14 games total missed by various players because of concussions in 2014. Bateman watched Seattle Seahawks games and read about Coach Pete Carroll's tackling philosophy. Carroll and assistant Rocky Seto were eschewing the age-old tackling dictums of planting your face mask in a runner's numbers if you were hitting him head-on or at least having your head on the upfield side of the runner if approaching from an angle. The Seahawks were using what they called the "Hawk" technique of attacking the runner's thighs with the defender's nearest shoulder, wrapping his legs with both arms and driving or rolling the runner to the ground. The technique is more popularly known as the "rugby" tackle because it's the method preferred by rugby players, who never wear helmets and need to keep their heads out of harm's way.

Bateman and his staff learned the rugby tackle and taught it to their players going into the 2015 season.

"The next year, we had one player miss a game with a head injury," Bateman says. "That's huge. There were always some things about tackling as it had been taught forever that didn't make sense to me. I'm supposed to run inside-out on the ball and then get my head across. That's physically impossible. That always caused me conflict. The game of football was so under attack, as a coach if you don't do something different, you're sticking your head in the sand. The last couple of years at Army, one or two kids missed one game for concussions and we're playing at a higher level and playing against better opponents. You say, 'Gosh, this has got to be a piece of it.'"

So far through spring practice, the Tar Heels think these coaching initiatives will pay off come Saturdays in the fall.

"I think [the 'Difference' period] has a great impact on the team," outside linebacker Tomon Fox says. "These drills help us finish, remind us of the importance of shedding blocks. We do them at the start every day, and once you get it in your head, it's going to make you do all those things in team periods, individual periods."

"Coach Bateman is tough and smart," safety Trey Morrison adds. "He's real hard on us, he wants everything perfect. I think we're making tackles in open space better. We're leveraging the ball, taking the proper angles, tracking the back hip. Every day, we're making progress. I think by next fall, we'll be really good."

It's only after emphasizing the importance of warding off blocks and taking runners to the ground with precision that Bateman even broaches the subject of scheme, and even then he says that identifying the Tar Heels' base as a "3-4" is almost superfluous.

"Scheme is a really over-rated thing," he says. "If our scheme is not multiple enough to put our best 11 on the field, then I should be fired. People say, 'Are you 3-4?' I say, 'Yeah, sure, we're 3-4, but we line up in everything.' It just depends on what's our best call and who are we playing? Last year, we were in two-down more than anything."

To wit, in the Tar Heels' scrimmage last Saturday, the first 10 defensive snaps showed Bateman using six different fronts (and only on two snaps were the Tar Heels in their "base" alignment). They played nine coverages and brought four different blitzes. What Bateman will say, though, is that the Tar Heels not play defense in a "Tampa 2" mode of having two deep safeties, playing lots of zone, trying to generate heat with four down linemen and keeping everything underneath.

"If you're just dropping in what I call 'vision coverage' where I'm seeing the ball and I'm breaking, you used to be able do that and be pretty good," he says. "The Tampa Bay Buccaneers won a Super Bowl doing that. Today, though, the ball comes out so fast and quarterbacks are so accurate and receivers are so good in space. You go tackle it and say you did a good job and you're second-and-four. I'm not great at math, but I know if they're doing that every time, they're going to get a first down.

"Our defense will be like rebel warriors, we kind of come from everywhere and we try to bait you into things, cause confusion, cause havoc, infiltrate from within. You try to create negative plays, you try to create incompletions, you try to create sacks. If you do that, you're in pretty good shape."

And the first rule: Everyone is a blitzer.

"I love it," says Morrison, a nickel back. "We can come from anywhere on the field. I've lined up everywhere this spring."

"I love being with coordinators who think 'attack,'" adds cornerbacks coach Dré Bly. "That's what Jay did at Army and that's what made him successful. We have a variety of looks and bring guys from all over the field. Our guys are embracing the moment and excited about this new opportunity."

One visitor to practice in early March was Sharper, who's now coaching at Georgetown University. He noted that Bateman's "fiery personality" had not dissipated in two decades and was amused to see Bateman nod toward Sharper and joke with his players that ex-NFL guys had nothing on him in high school.

"Then he was showing tackling technique and instead of talking about it, he rolled into Dré Bly and took him to the ground," Sharper says. "He's still got that energy, he's still throwing his body around and tackling another coach. He's definitely bringing the pressure. Those kids will enjoy bringing that pressure."

Chapel Hill writer Lee Pace has been covering Tar Heel football with his "Extra Points" column since 1990 and in 2016 published the definitive history of Kenan Stadium, "Football in a Forest." Follow him @LeePaceTweet and write him at leepace7@gmail.com

Players Mentioned

MBB: Hubert Davis Pre-Georgia Tech Press Conference

Friday, January 30

Carolina Insider - Interview with Megan Streicher (Full Segment) - January 30, 2026

Friday, January 30

WBB: Courtney Banghart Pre-NC State Media Availability

Friday, January 30

UNC Men's Basketball: Tar Heels Battle Back to Top #14 Virginia, 85-80

Saturday, January 24